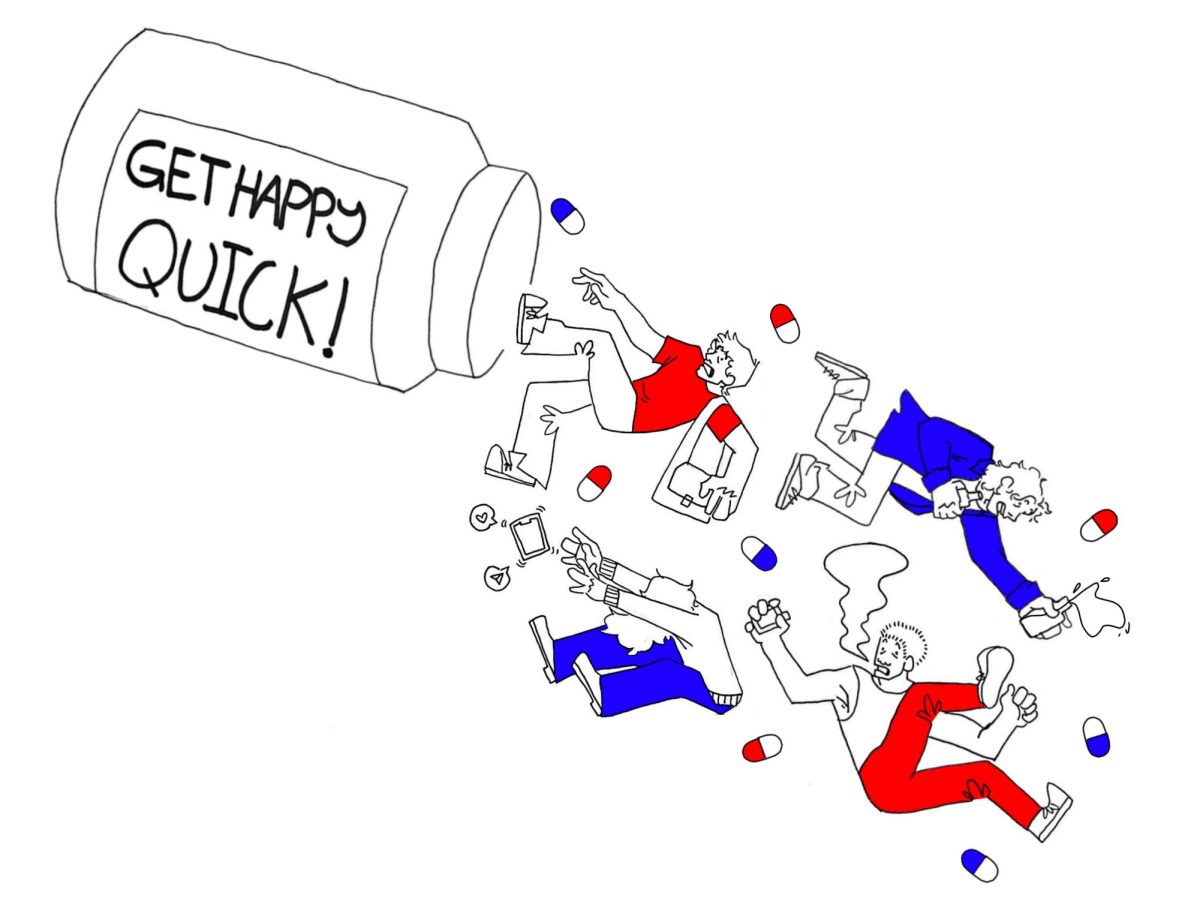

Pleasure and excitement are two of the most primary drivers in human motivation. They ignite us with the energy to accomplish small goals – getting up in the morning or finishing an assignment – as well as those that require more intention: a career, a hobby or working to accomplish a long-held resolution.

More specifically, the bursts of satisfaction we experience are driven by chemical messages through the neural structure of our brain’s reward system, those chemicals being dopamine.

While dopamine release isn’t the only factor to instigate an addiction, it plays a large role in the habits formed around activities that quickly reward the brain: scrolling on one’s phone or partaking in substances like drugs and alcohol.

Mackenzie Fee, school social worker, explained the relationship in our bodies between habits and chemical rewards.

“When people use substances, it impacts the reward and pleasure part of our brain,” Fee said. “Generally, the more often a behavior is repeated, the stronger the brain responds to the behavior.”

Habits like these, whether softly classified as attachments, or slotted into the category of standard addictions, are ever important to examine as settling dust of New Year’s resolutions couples with a changing sensory world.

In today’s neurological landscape, there are more ways to get passive pleasure than just from drugs and alcohol, begging the question of how BHS students are experiencing substance use, and how long-lasting fulfillment differs from the spike of heightened dopamine.

An anonymous student shared their opinions on quick versus sustainable joy and how that pleasure is easily activated with the use of technology.

“Going on my phone is like a little boost, and I wouldn’t say it’s exactly good for you,” the student said. “A long term rush is like having a conversation with someone; it can give you a lasting memory that you could think back on fondly.”

Through conversation with other students, the use of phones and social media, though rewarding on surface level, don’t seem to sustain genuine interest for very long.

“I’ll pretty quickly lose interest in whatever I’m looking at on my phone,” a student said. “But something keeps me glued to it, especially on reels where I can scroll and there’s always more.”

According to Andrew Huberman, host of the neuroscience podcast “Huberman Lab,” this act of seeking rewards through continuing an action (such as scrolling on one’s phone) is called dopamine chasing.

Consequently, when a feeling of euphoria is achieved often from these pleasurable activities – this could be from drinking alcohol, playing video games or even just eating food – the chronic overstimulation can lead to the brain compensating by reducing the sensitivity of its dopamine receptors, or even reducing the number of receptors overtime.

Biology teacher Kaija Reinelt has seen this pattern of excitement seeking in her classroom, where she believes student phone use plays a major role.

“I’ve definitely noticed that students who need stimulation all the time, oftentimes have a more dependent relationship with their phone,” Reinelt said. “Which I don’t think is inherently a bad thing. It’s just something people need to learn how to manage based on how their brain functions.”

Although our reactions to the hyper stimulation of phones vary person to person, Reinelt believes anyone can benefit from unplugging and reconsidering their relationship to technology.

“Boredom can lead to creativity, and more time for your brain to just unpack life,” Reinelt said. “I think if you’re not being intentional about creating that type of time for yourself to be reflective without adding more input, it can really impact your ability to set goals or have a vision for the future.”

Partaking in screen use isn’t the only addiction students are reconsidering. An anonymous student conveyed their relationship, past and present, with alcohol and how it impacted their ability to find outward fulfillment.

“I don’t like the feeling of alcohol, it just doesn’t make me feel like myself,” the student said. “But for a while I couldn’t go more than two days without drinking. It made me feel kind of disappointed that that’s how I’m spending my time.”

Alcohol, like technology, can lead to the drop of baseline dopamine levels (known as downregulation) when consumed often. This is what causes the lack of motivation people accustomed to drinking can experience while sober, making it difficult to proceed with normal routines.

“The short term is just the chemical reaction. But in the long-term you realize it’s derailing the daily habits you try to implement,” The student said.

According to the “Huberman Lab,” this downregulation also contributes to building a

tolerance to alcohol, as the effects of both alcohol and dopamine mitigate the more often we are exposed to them.

“In the short term, cognitive abilities like memory, attention, and concentration are impaired,” Fee said. “When students experience this long term, their ability to develop critical thinking and problem-solving skills decreases.”

A student’s story aligned with Fee’s detailing of substance use, and how it impacts the ability to focus on certain aspects of life.

“I had trouble focusing on the right things because I was living with that big emphasis on drinking,” a student said. “Long-term happiness is dependent on working at continuous goals. Drinking gets in the way of that and it doesn’t make me feel as accomplished.”

This then poses the question of how to overcome such habits of addiction. Whether the dependence is physical or psychological, the cognitive dissonance of wanting to change a habit, but not knowing how, requires skills to overcome. In the case of addictive phone use, Counselor Sonja Petersen feels that organization and physical distance may be the best solutions.

“I think that if a student is concerned that their phone may be impacting motivation, a couple of things to try might be putting their phone in a different room for periods of time,” Pertersen said. “Another thing students can try when they feel a lack of motivation is to break tasks into smaller, manageable chunks to reduce feelings of being overwhelmed.”

Fee’s process for helping students with other addictions, though different in nature, relies on a similar practice of breaking things down into more sizable pieces.

“To change habits, you need to find sustainable ways to change,” Fee said. “This usually means taking a multi-faceted approach: engaging in family support, skill building, setting goals, changing peer groups, each targeting one area of problem.”