The Idealization of Female Pain

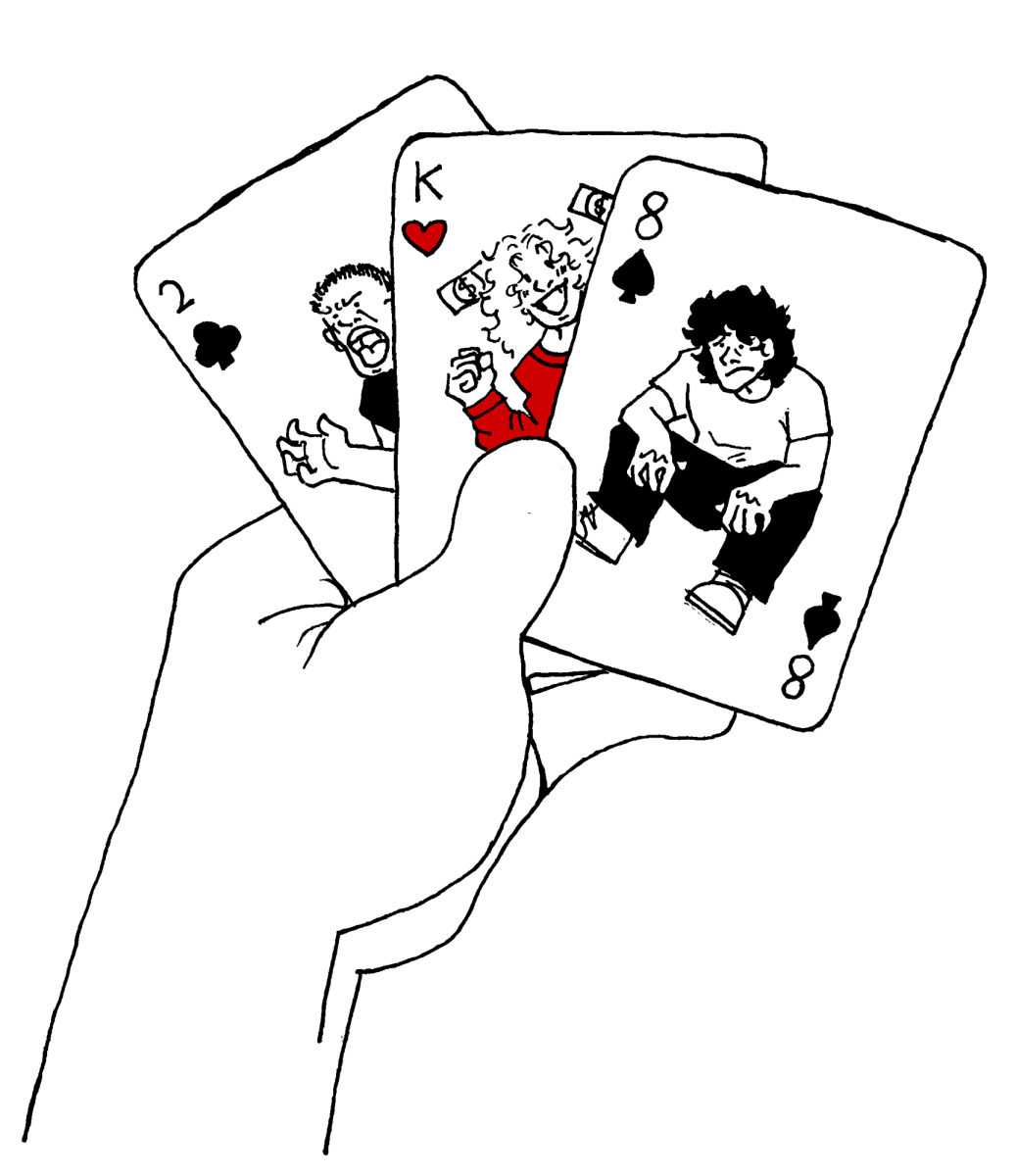

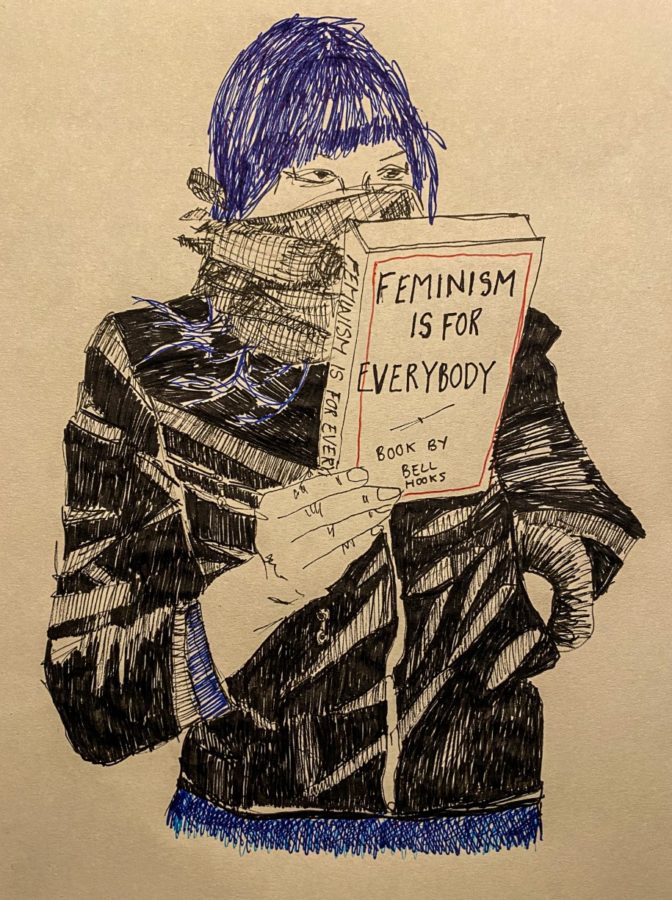

Cartoon by Lina McRoberts, president of Feminist Club, Adoptee & Foster Club and Model United Nations.

April 23, 2023

In the early months of 2022, I found myself in the alcoves of a prodigious depressive episode – the kind that straps weights to your wrists and makes you question everybody’s very existence. I spent most of my days studying to distract from this existential thrall. However, when that became too much of a burden, I resorted to lying quietly on my bed, staring at the ceiling, and listening to various audiobooks – justifying this as merely an extension of my studying. I often found it difficult to distinguish when I was dreaming from when I was awake.

I am in my “My Year of Rest and Relaxation” era: unhinged. I am waking at erratic hours, I am weeping, I am writing and never rioting, I am seeing shapes on the map on my wall. I am never washing my face, I am consuming, I am laying waste to my reputation. I am remembering to walk into my kitchen, barefoot and hair-down with a groggy expression on my face, so I’ll sound sexy in my memoir. Even when I was purportedly at my lowest, I was filtering my experiences through the eyes of the watcher within (thank you, Atwood). The yearn to editorialize our experiences – to glamorize the “unseen” and live for our yet-to-be-written-biographies — has become an inevitable trait of womanhood, as inescapable as breathing.

At its core though, the romanticization of woman’s suffering has less to do with the actual suffering, and more with public analyses and internalized avoidance. Nobody will admit it, but what nearly everyone wants is for women to be in excruciating pain, and then proceed to kill themselves before they can begin to complain. They would rather we be sad but dead so somebody can write about how beautifully heart-broken we were. Women are intended to be mythology without autonomy; and in our attempts to be desired, we play into the Woman in Pain archetype.

Does anyone want me? They must, because I am here and I am alive, right? I think I love to suffer, and I want to make sure that I am suffering just the right amount: not enough to be labeled as crazy or mentally ill, but enough to give the illusion that I am unknowing of my hysterics, delicate in my pain. Am I suffering beautifully? I hope so. And within those two sentences you, my dear readers, may see that I have a voyeuristic relationship with my own agony. But then again, what woman does not? What woman does not secretly play “the fool”, “the innocent”, “the immature”? What woman does not gasp in amazement at a shirtless chest or flush at stories of past sexual conquests? There is something uncomfortably liberating in playing the damsel in distress.

Pain, at first physical and later emotional, is an essential part of the female grooming process, and that is not accidental. Plucking our eyebrows, shaving under the arms, learning to walk in high-heeled shoes. The pain teaches an important lesson: that no price is too great, no process too repulsive, no change too painful for a woman to be beautiful. The tolerance of this pain and the romanticization of that toleration begins here in adolescents, and serves to prepare girls for lives of childbearing, self-indignation, and husband-pleasing.

The male response to the woman’s pain, of being made up and bound, is thus a learned fetish. As such, romance becomes role-differentiation: superiority based on culturally enforced inferiority. And yet, we as women continue to play into this archetype. But god, it feels so good to be understood, if only as a caricature. I would be lying if I were to say that I do not find great comfort in my femininity. I like being small and purportedly frail; I like the fact that I am able to see my collar bones and tie up my purposely unkempt hair. Concurrently however, knowing that I can philosophize, reflect, analyze, and write provides with solidity and reinforcement, an invisible bedrock rightness that reassures me, just as it is reassuring to know that below me blue whales swim, placid in faraway waters, that I am here, that I am alive, and that that is okay.

The question then becomes, is it possible to play into this inferior archetype while simultaneously obtaining equality – and the answer, quite clearly, is a resounding no. It is impossible to attain equality within an intrinsically unequal society. And yet, try as I might, I can only seem to understand myself through the fantasies of my supposed pain – and, just as I reassure myself that my self-destructive tendencies are some sort of built-in, inherent sense of self, I cannot help but wonder, to what extent are they creating me too. Who would we be if we confronted our rage, and would it be enough?

The idealization of our pain may be an inevitable facet of womanhood, or it may be a narcissistic tendency of the masochistic egocentric. Whatever it may be, it strikes me as remarkable that when women hurt, we are forced to bear the burden of proof not only to the outside world, but to ourselves as well.