The pitfalls of the Body Positivity movement: Confidence and empowerment aren’t the cure for systemic discrimination

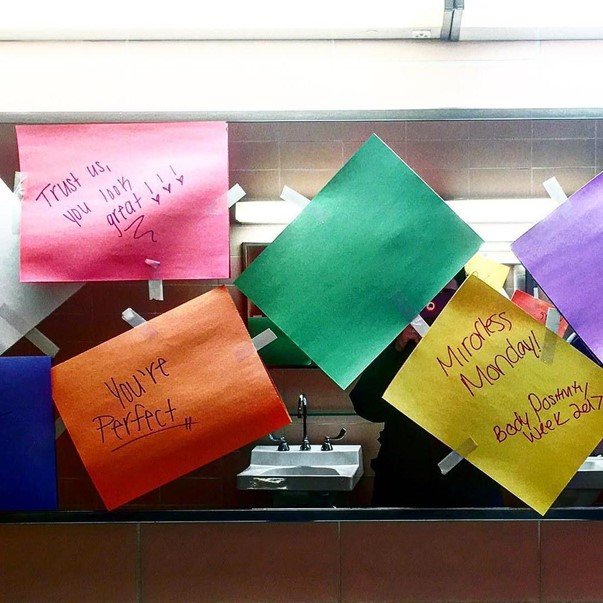

Source: Licensed under creative commons. By Villa Maria College. Marked with CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

A lot of body positive imagery is advertising for large companies. This is one of the few images of the simple positivity exemplified by the movement, while staying separate from the commercial center of the current movement.

March 10, 2022

The term body positivity and the movement surrounding it has been on the rise in popularity since around 2010, and it’s easy to see why. The word positivity invokes images of a happy, carefree life and most associated images feature beautiful women, laughing and rejoicing in their newfound empowerment.

On Instagram, a quick search of #bodypositive will bring up thousands of posts and show thousands of people proudly displaying their bodies. The hashtag is now primarily used by thin white women, their fitness inspiration and thirst traps taking up more space on the page than anything else.

This is a far cry from the original activist’s objectives and intent of the movement.

A Brief History of Body Positivity

The fat acceptance/fat liberation movement, the predecessor to the body positive movement of today, was started in the 1960s. One of the most prominent actions of the early movement was a “fat-in,” where hundreds of people came together to burn diet books, eat and protest against discrimination.

Like most social movements, there were internal debates about how to approach activism. The National Association to Advance Fat Acceptance (NAAFA) focused on letter writing and legal action, whereas the Fat Underground was notably more radical.

The movement was significantly more intersectional than the body positivity movement of today, because it was primarily created by queer and Black fat women who recognized the intersection between their struggles and the way discrimination against them compounded. Welfare rights activist Johnnie Tillmon spoke on such intersections.

“I’m a woman. I’m a Black woman. I’m a poor woman. I’m a fat woman. I’m a middle-aged woman. In this country, if you’re any one of those things you count less as a human being,” Tillmon said.

White women, like some in the Fat Underground, allied themselves with other movements, instead of distancing themselves. Judy Freespirit and Sara Aldebaran, two members of the Fat Underground, did so in their “Fat Liberation Manifesto.”

“We see our struggle as allied with the struggle of other oppressed groups, against classism, racism, sexism, ageism, capitalism, imperialism, and the like,” Freespirit and Aldebaran wrote.

One of the largest differences between fat liberation and body positivity was the distinctly anti-capitalist tone of the first movement.

“We are angry at the mistreatment by commercial and sexist interests. These have exploited our bodies as objects of ridicule, thereby creating an immensely profitable market selling the false promise of avoidance of, or relief from, that ridicule,” Freespirit and Aldebaran wrote.

Once, fat liberation critiqued commercialization. Now, mainstream body positivity benefits from consumer culture.

Problems with the Body Positivity Movement

One of the most iconic body positive moments of the 21st century was the Dove Real Beauty campaign, started in 2004. The campaign featured critiques of photoshop, women learning to love themselves, and women of slightly different body types standing around in underwear (now a staple of #bodypositive marketing).

Although there were some negative responses, the advertisement was hugely successful and taught the marketing world to embrace general progressive messages for profit. Corporations began reworking feminist messages to suit their own interests (e.g., Stick it to the man! Buy this lipstick for you!) and commercialized “girl power” body positivity began to rise.

Outside of materialistic and corporate body positivity, another large problem in the movement is how body shaming and fatphobia are treated as the same issue. Body shaming is never acceptable, but thin shaming is not comparable to fatphobia.

There is no systemic discrimination of thin people. People do not lose jobs or access to proper health care because they are too thin, whereas fat people are often misdiagnosed, ignored and underpaid (or are never hired in the first place) because of their weight.

Confidence-based messaging, like that used in a lot of body positivity advertising, ignores the very real implications of why some fat people want to lose weight or why some thin people want to avoid gaining weight. The role of societal pressures and beauty standards are mentioned, but they’re spoken of as though they are social pressures that just affect people’s self esteem, not their livelihoods or health.

At its best, the focus of the current body positivity movement is helping people dismantle personal body image issues and championing self acceptance and positivity, so people (primarily women) can be more confident. These aren’t bad goals, in fact the movement and messaging around self love and body acceptance have likely done a world of good for many. The problem with these goals is the focus on internal, personal change as opposed to systemic reform.

Vox journalist Amanda Mull connected this concept to the infamous Dove advertisement.

“The urge to talk about a broad cultural problem while refusing to name a bad actor left the blame squarely on the shoulders of the women who had the temerity not to love themselves sufficiently,” Mull said.

Empowerment Isn’t Enough

Outside of the body positive movement, the landscape of most mainstream feminism and social activism has the same problem. When activism is commercialized or diluted to increase public appeal, the complexity and nuance of the issues are flattened.

The message becomes about self-starting, working hard to overcome, and being confident in yourself, while the larger societal forces that maintain inequality are sugar coated or glossed over. New, scary topics are easier to handle that way, when the solution is clear and personal instead of challenging and societal.

In short, the appeal of the body positivity movement — the simplicity, positivity and easily digestible, commodifiable aesthetic — is exactly why the movement is so insidious.

The constant barrage of aggressive positivity not only flattens nuance, it can make people who are struggling feel worse. It appears that everyone else is effortlessly happy and the reader of said messages is the problem, the only one who isn’t smart enough to love themself.

This isn’t to put all responsibility for problems with activism on corporations or make it seem like individual actions aren’t impactful. Changes in the social landscape, like those brought about by advertising and social media are incredibly useful for larger scale change.

My main point is that there needs to be more nuance in the discussion around weight, presentation and empowerment.

Teenagers especially, should be critical of large corporate actions related to social justice in order to avoid falling victim to the oversimplified, commercialized view of empowerment. This view leads people to buy so called feminist miracle products to make change and feel better about themselves, as opposed to take action against the systemic and social forces that perpetuate such issues.

Not only does the corporate approach to activism help business over people, it spreads active harm, by taking away from the original, radical intents of social movements in favor of simply rebranding the status quo for an illusion of progress.

Large scale systemic reform isn’t a reasonable request for individual people, but that doesn’t meaning giving up or buying a ‘#LoveYourself’ Forever 21 T-shirt are the best options. Individuals can support smaller creators, particularly those who are POC, disabled, and LGBTQ+, donate to anti-fatphobia organizations, or simply continue nuanced, challenging conversations about societal issues in their personal lives.