The perpetuation of racism among educators negatively affects students of color

Dhani Srinivasan and Samantha Margot, Staff Reporters

Originally published March 8, 2019

Fletcher Anderson

Students, particularly high school students, rant and rave about their teachers, whether it be the workload or their professional attitude. On the flip side, a teacher can sit down after a long day and grandstand about students who refuse to adhere to their rules.

Jump.

How high?

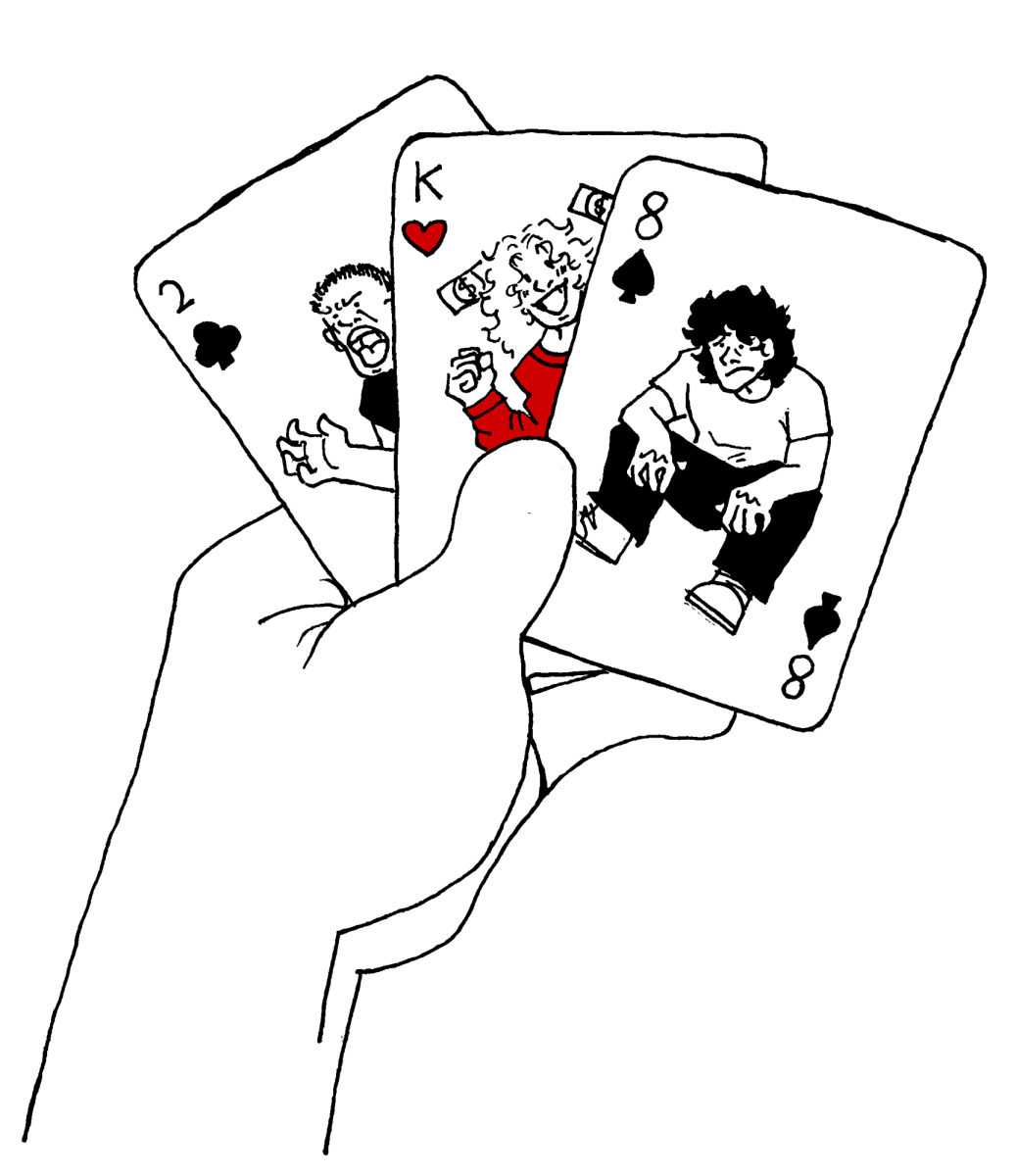

It comes down to power. Both parties have it and know how to leverage it. One side vies for the good grade, the other craves the attention of its pupils.

Such causes can only come from balancing the scales. Respect, power and fear go hand in hand down a two way street.

In racially charged America, it’s easy for the scales to tip.

Power imbalances are common, ranging from dictatorship of the government to ignorance in the classroom. Between students of color and white teachers, the power differentials are magnified and can have significant long term consequences. When “racially charged” incidents do transpire, there are barriers that prevent students of color from talking to their teachers.

What prevents conversation

Perhaps some barriers stem from the widespread and systematic manner that black students are disproportionately disciplined. According to a report released by the Justice Department, in 2015-2016 black students represented 15% of all enrolled students and accounted for 31% of children referred to police or arrested.

Or it could be the constant barrage of microaggressions that prevents students from having comfortable relationships with their teachers. Within the confines of the classroom, Senior Rose Kranwinkle has been marginalized due to her Asian American identity.

“It was almost as if it barely slipped under the radar,” Kranwinkle said about a recent racially charged incident with a teacher. “Sometimes I don’t want to speak up because they are in a place of power over me.”

Kranwinkle also felt that the teacher could subconsciously harbor ill feelings if they were reported to administration, leading to a possible drop in grades.

“In that case, at the time during class they have the power over my grade and they have the power to say ‘oh, she’s just a bad student, she has an attitude.’ In that case I wanted to speak up but I didn’t feel like I necessarily could.”

Ignoring racist incidents

If one is able to get over the mental hurdle and confront the teacher, there is no telling how they will react. It seems that many teachers see that distancing themselves from race and racism in the classroom (namely between students) makes them “not racist.” Dr. Larry J. Walker discusses the impact teachers have when they choose not to address the conflict.

“Sometimes educators choose to overlook racial incidents in classrooms or school settings that increase hostilities,” said Walker in an Education Week Classroom Q&A. “Turning a blind eye to intolerance can lead to serious long-term problems for subgroups including anxiety and mental health challenges. Recognizing that racism is tangible is a necessary step to address a contentious issue.”

Racism in the classroom

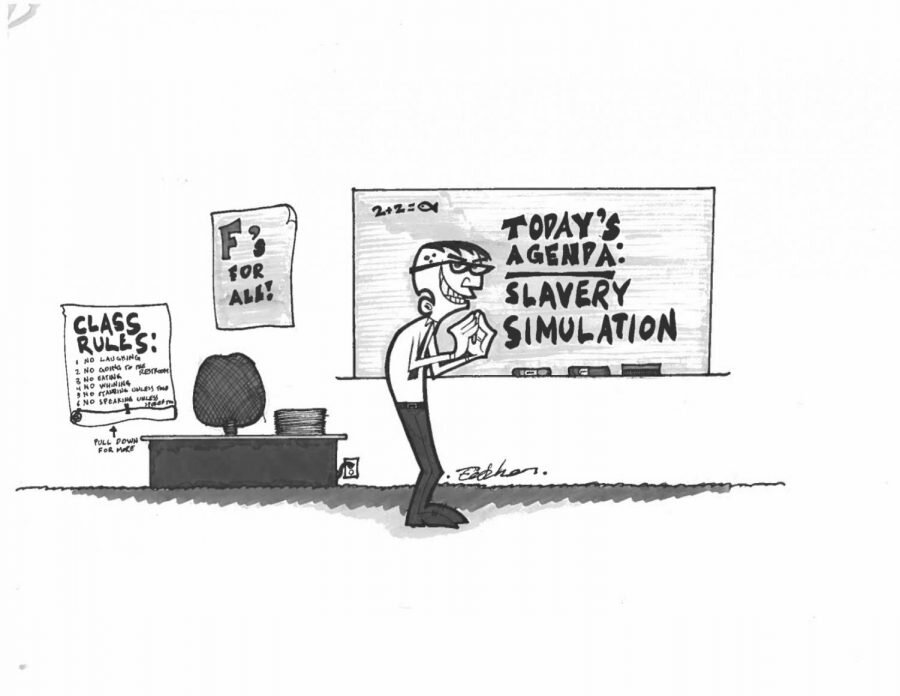

Across the nation, there have been reports of racist incidents in classrooms. Teaching Tolerance, a web based magazine for educators creating tolerance based curriculum, recorded 496 reports in 47 states involving hate and bias incidents in schools. A startling 81 percent of these events were racist in nature, and within the classroom 138 hate incidents were reported.

It could be teachers themselves perpetuating racism: just last week, a Virginian class was instructed to partake in a ‘runaway slave game’ during P.E. class. Or it could be between students, with a white student calling a black student the n-word.

Recently, within our own school, a historical re-enactment was performed by students that blatantly perpetuated racial stereotypes. Some students looked at each other abashed while others laughed; the teacher seemed to not bat an eye.

Students later went to said teacher in hopes that they would use the incident as a valuable opportunity to talk about race. However, the students found that the teacher’s response–and later the administration’s–was to distance themselves from any responsibility and complicity from this discourse of racism in the classroom.

Instead of using their authority in the classroom as a white, male, teacher to address the students, the teacher chose to ignore discussing the event, even though it explicitly and negatively affected students of color in the room.

The objective goal of the classroom is to prepare students for life. Unconscious isolation and making students of color feel less-than should not be acceptable conditions to prepare one for the fulfilling and educated lifestyle promoted by schools. In any school that aims to bolster inclusion and connectivity, these habits need to be broken lest they cause danger to someone’s physical or mental well being.

Creating a power balance

Despite instances like this, there are a few examples of white teachers consciously working to shift power dynamics within the classroom.

Taryn Coe, a ninth grade ELA teacher, makes a point to explicitly talk about issues of race within the class curriculum. She teaches a unit called “Race in America” where students read and analyze works by authors of color surrounding issues of race.

During her first year of teaching “Race in America,” Coe remembers a student of color approaching her after a seminar on white privilege.

“There was one student that came to me and said that she felt really uncomfortable and that she didn’t want to say anything even though she was interested in the issues because she felt she would be judged as the only student of color,” Coe said. “I thought this was interesting because her perception was that she was the only student of color in the room, even though there were a couple others.”

That’s often how it can feel in a predominantly white school. Coe describes that she later reshaped the unit to try to make her students of color more comfortable.

“It’s one of the reasons that I, in later units, have been checking in with students of color in advance of those types of discussion to see how they are feeling and to offer them support. I had gone into that seminar thinking that even though there weren’t many students of color in the classroom, there were a few and maybe they’d be supporting each other. But she was feeling really isolated.”

The objective goal of the classroom is to prepare students for life. Unconscious isolation and making students of color feel less-than should not be acceptable conditions to prepare one for the fulfilling and educated lifestyle promoted by schools. In any school that aims to bolster inclusion and connectivity, these habits need to be broken lest they cause danger to someone’s physical or mental well being.

It’s easy to understand that talking about race can be uncomfortable and teachers already have a difficult job. But avoiding racially charged incidents in the classroom can become more marginalizing to students of color–especially in predominantly white schools.