America’s SAT system favors wealthier students

Annelise Bowser and Claude Brun

Originally published March 29, 2018

Very few students look forward to taking the SAT. The nation-wide, 4-hour-long assessment that we’ve supposedly spent the last 11 years in the American education system preparing for isn’t technically a college requirement, but it might as well be. For many of us, it’s taken for granted that we take the SAT; our school provides it for free and many students take prep classes or even take the test a second time in order to get the best score possible to boast on their ever-nearing college applications.

The education-industrial complex

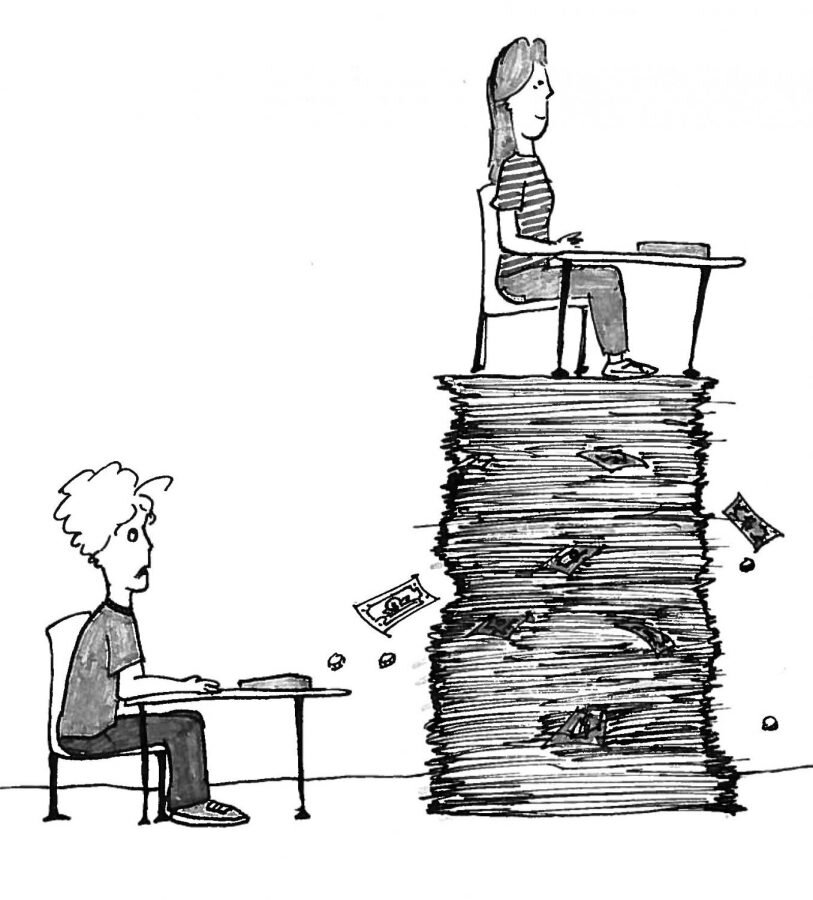

However, in our insular community, we don’t often consider the inequalities that lurk behind the huge corporate standardized testing system. Many schools have made an enormous step towards equity by offering the SAT for free to all juniors, but that doesn’t fully counteract the reality that the test still offers a competitive advantage to students in higher economic classes.

Lisa Coacher is a language arts teacher who coordinates standardized testing. “Students who have a higher economic background are able to pay for SAT prep classes,” Coacher said.

While students can study for the SAT by buying review books and taking online courses, in-person prep classes or private tutors seem to be the most effective. These options range from $20 to an upwards of a thousand, and it’s not hard to tell which is going to improve test scores the most.

The University of Washington’s Women’s Center offers a month-long course for $150, but Kaplan’s comprehensive course consisting of eight 3-hour classes costs around $1,000. Even pricier, a private tutor can easily charge $60 an hour or more.

Many middle-to-upper class students have the privilege of affording the classes that promise to add at least a hundred points to their SAT score, but for students whose families don’t have that extra money, paying $150 to $1000 for a prep class so that they can raise their score and make it into their dream college just isn’t feasible.

“It’s supposed to be fair but there’s a lot of research out there that says it’s not accessible for students of poor economic backgrounds so they do say there’s some bias in there,” Coacher says.

And that’s where the problem is.

Stifled by income

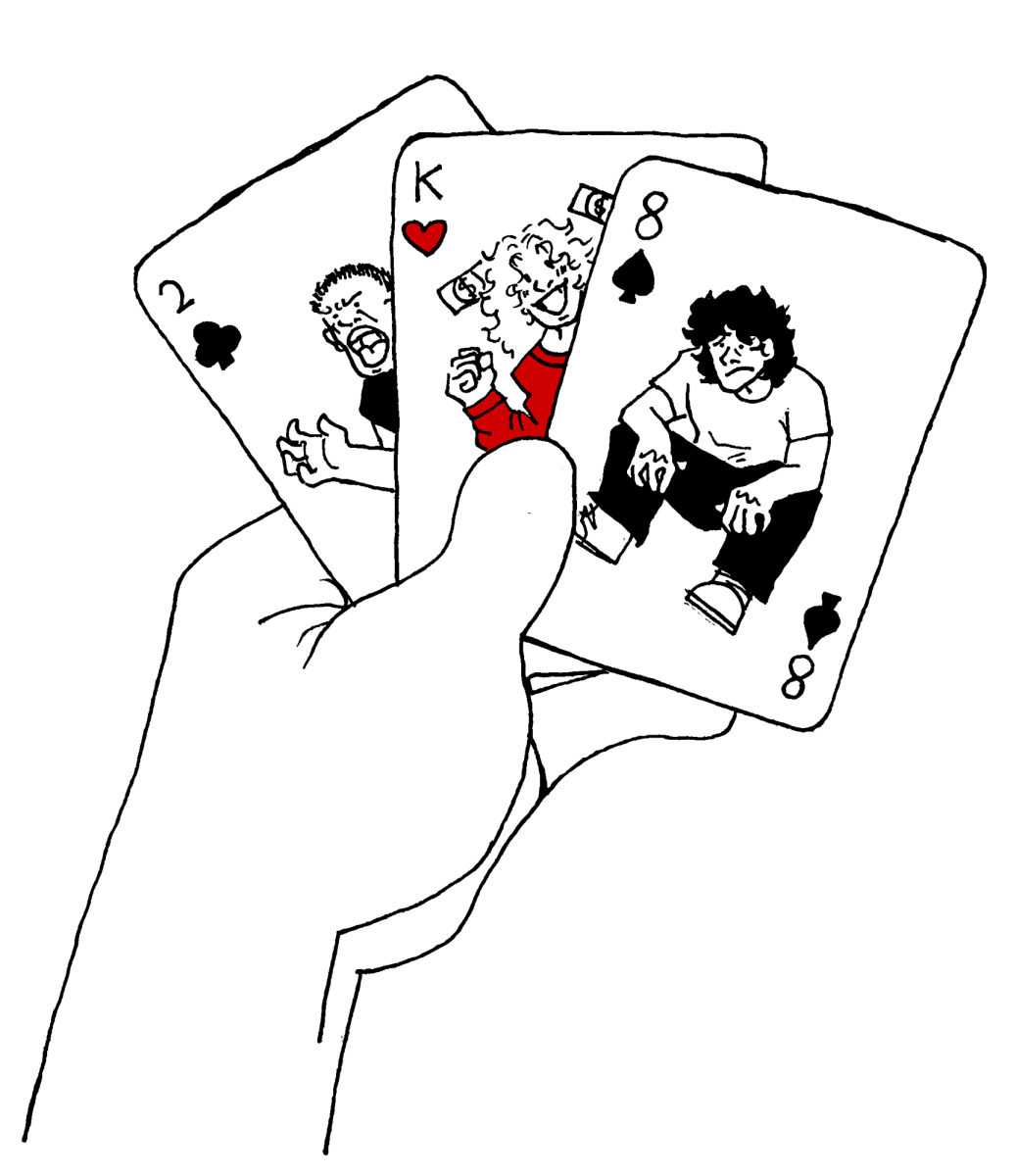

As some students pay to unlock the secrets to getting a higher score, students who can’t pay are left at a disadvantage because of something they have no control over: their family’s income.

Research shows that SAT scores are highly correlated with family income—richer students get higher scores. This is a generalization, of course; there are stupid rich kids and genius poor kids that don’t fit the model, but the correlation is undeniable.

The SAT costs $46 without the essay portion and $60 with it. It seems unfair that someone has to pay for a test that’s essentially a requirement to get into a college that will almost guarantee a well-paying job.

Corporate-run education

The SAT is organized by the College Board, which is owned by Pearson Education, who also owns the Common Core, various educational media brands and even Poptropica, of all things. Pearson is a corporation like any other—its main goal is to gain profit, not to ensure a fair educational environment for all students, regardless of their ability to pay. Sadly, it just so happens that they make their profit by charging a great deal of money for not only the SAT, but also AP exams, which cost $105 each.

At least Pearson doesn’t hide the fact that they’re a corporate interest—they just quietly control nearly every aspect of the standardized American public education system and make a killing off of it. In 2017, Pearson Education’s net income was over $500 million.

In recent years, the Pearson-owned College Board has partnered with Khan Academy to offer free SAT prep online, but that still doesn’t give students without at-home computer access any easily attainable way to prepare for the test. While this is a step in the right direction, it seems like too little, too late, as it will take time for students across the nation to embrace the free programs provided by Khan Academy and these programs still aren’t accessible to all.

Many students in lower economic classes have to work after school to support their families, so they may not have the time to take advantage of Khan Academy’s free programs. Furthermore, “students still need to be self-disciplined to do it on their own,” Coacher said.

While we shouldn’t necessarily demonize Pearson, we should question whether we want our free American public education system to be controlled by a for-profit corporation.

Public education is, theoretically, free, which is supposed to put students on equal footing. But when the basic structure of the national educational system is controlled by corporate interests who charge money for the programs that help students excel after high school, we must ask ourselves whether this system really has students’ best interests at heart.