Students and teachers comment on educational distinctions

Jaya Flanary and Tess Harstrick, Features Editor and News Editor

Originally published February 27, 2015

Simon Gibson Penrose

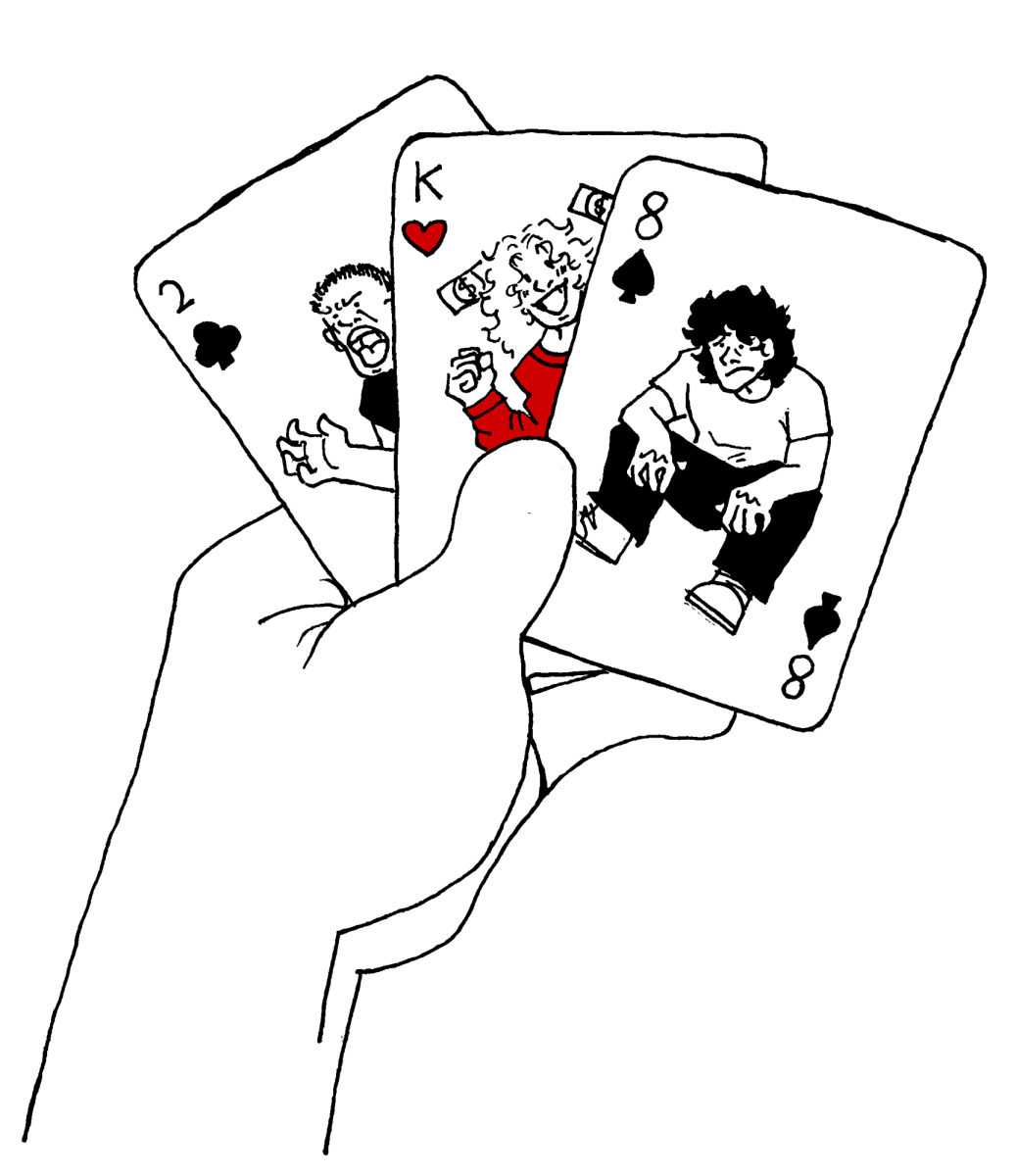

Every year, students choose their classes for the next year based on their interests, college applications or their level of difficulty. Students choose courses so they might better succeed in high school and they show colleges, parents or themselves, what they are capable of.

Sometimes, students choose courses and secretly or outwardly hope for one teacher over another. Whether favoritism or fear of a lower grade, reputations about teachers are present in high school, specifically between the same classes with different teachers.

While no distinctions between these classes are intended, distinctions emerge because of teaching styles, workload and grading methods.

According to counselor Tom Kramer, the most-dropped classes are electives, due to students signing up for electives they’re not interested in or end up disliking. But some students drop or switch out of core classes.

“We’re trying to encourage responsible planning,” Kramer said. “We don’t change, for the most part, for teacher preference.”

Dropped classes range from random electives to courses such as AP United States History (APUSH) and Physics, though the majority of students will drop an elective or a class they feel they’re in the wrong level of, like a language or math.

According to new physics teacher Thomas Haff, a student drops a class for a variety of reasons such as being unprepared for a course, disliking a course, feeling excluded, disliking a teacher, home issues and more.

AP English Language and Composition teachers Brian Reardon and Kristin Storey found that struggling students first approach counselors. “I understand students find teachers intimidating and don’t like to do that,” Storey said. “And I wouldn’t be surprised if I had an intimidating personality. Strong personality.”

A few years ago there was an exodus from teacher Dina McArdle’s APUSH class. McArdle’s opposing teacher Pam Hering was new to APUSH, and a rumor had circulated that it was easier to receive an A in Hering’s class than in McArdle’s. Students began transferring from McArdle’s to Hering’s, or in other words, from one APUSH class to another.

“There was this competition between her and me,” McArdle said. “I started to really look at what was going on. And it’s true, that I was really hard… It was good because I had to look and then Ms. Hering had to look at what she was doing… we balanced it out a little.”

Some teachers have also directly tried to solve the problem of courses being dissimilar because of teachers’ different styles or decisions. Teachers who teach the same courses collaborate to even out the level of difficulty of their classes to maintain a fairness in how students are learning. Reardon and Storey, for example, talk nearly every day to compare lesson plans and student feedback.

“It’s better that people should work more collaboratively,” McArdle said. “I think programs should be kind of consistent.”

But the struggle to keep courses equal remains. There are many courses taught by two teachers, such as APLA 11, APUSH, Physics and various others. So the question arises, how can courses remain similar, giving all students an equal chance to succeed, when teachers have different styles of teaching?

Is it inevitable that two classes of the same curriculum will never truly be equal? And should this equality matter, or should students persevere through the course they signed up for, despite teaching style preferences?

Haff, who works parallel to physics teacher Eric Muhs, believes that Muhs’ class is project oriented, while his own mathematics, or “mechanics,” semester has been considerably textbook-based. Haff’s classroom is also located in the math pod, therefore the environment is much different than Muhs’ lab orientated room.

“We [Haff and Muhs] have to mirror each other with ideas,” Haff said. “He might take one path, I might take another, we both end up in Rome.”

Some students found difficulty with Haff’s teaching philosophy and style. “I don’t think Haff’s aware of the difference [between his class and Muhs’s], but he treats his class like a college prep class, and that’s not what a lot of people signed up for,” junior Bella Anderson, a student of Haff’s before she dropped the class, said. “There was a disconnect, for sure.”

While there is often no indicator for how difficult a class should be, many believe they should follow the same curriculum. “Sometimes it creates unhappiness between students [when curriculums differ],” junior Gabriella Kimmerly said.

AP European History teacher Alicia Hale is well aware of the reputation her class holds within the student body. “I don’t take pride in some of the really horrible things people say about my class, like how hard it is, how mean I am. Because I don’t think that’s true,” Hale said. “My class is hard because you have to work hard. My class is hard because it’s an AP class. I don’t go home at night and plot the demise of my students’ GPA. It should be hard.”

However, Hale’s class stands alone in its category, as the other choices are World History or AP World, classes with vastly different curriculums. Kimmerly strongly believes that classes with the different curriculums have more responsibility to make their courses equal. “Their curriculums should have similar end goals,” Kimmerly said. “When there’s different workloads some kids think they’re not getting as good of an education.”

Reardon does not give much credence to what he hears of other teachers. “I always take student comments about teachers with a grain of salt,” Reardon said. “I don’t ever want to assume that what I hear from students about any given teacher is the whole truth.”

Storey shares Reardons view regarding student comments. “I’ve heard rumors that I don’t give A’s,” Storey said. “It would make me crazy if I tried to think all the time about what people think of me. I try and be upfront, I try and be honest, I try and be transparent. I don’t try and trick kids. I’m here to help them grow.”

Most teachers won’t see a student dropping their class as a personal reflection on themselves, but some do take it personally. “Today in sixth period when kids were teasing about like, ‘so and so’s not here today they just hate your class’ or whatever, of course, you’re just like, ‘I can’t believe that,’” McArdle said. “When people drop you always think, ‘What went wrong? What did I do wrong?’”