A nostalgic rollercoaster

Coleman Andersen, Opinions Editor

Originally published October 8, 2014

“Boyhood” gave me memory loss. Why?

Because I’ve argued with my sister. I’ve moved and switched schools and wrestled with change. I’ve grown out my hair and have been forced to have it cut. I’ve gone to baseball games with my dad. I’ve gone to parties, struggled with the meaning of life.

Now when I think about my first Mariners game, I can only remember Mason (Ellar Coltrane) screaming alongside his dad (Ethan Hawke).

I lived what Richard Linklater, director, wrote and filmed. My mind and his movie have melded. It’s weird, but it’s also the ultimate testament to the universality of “Boyhood’s” coming of age story.

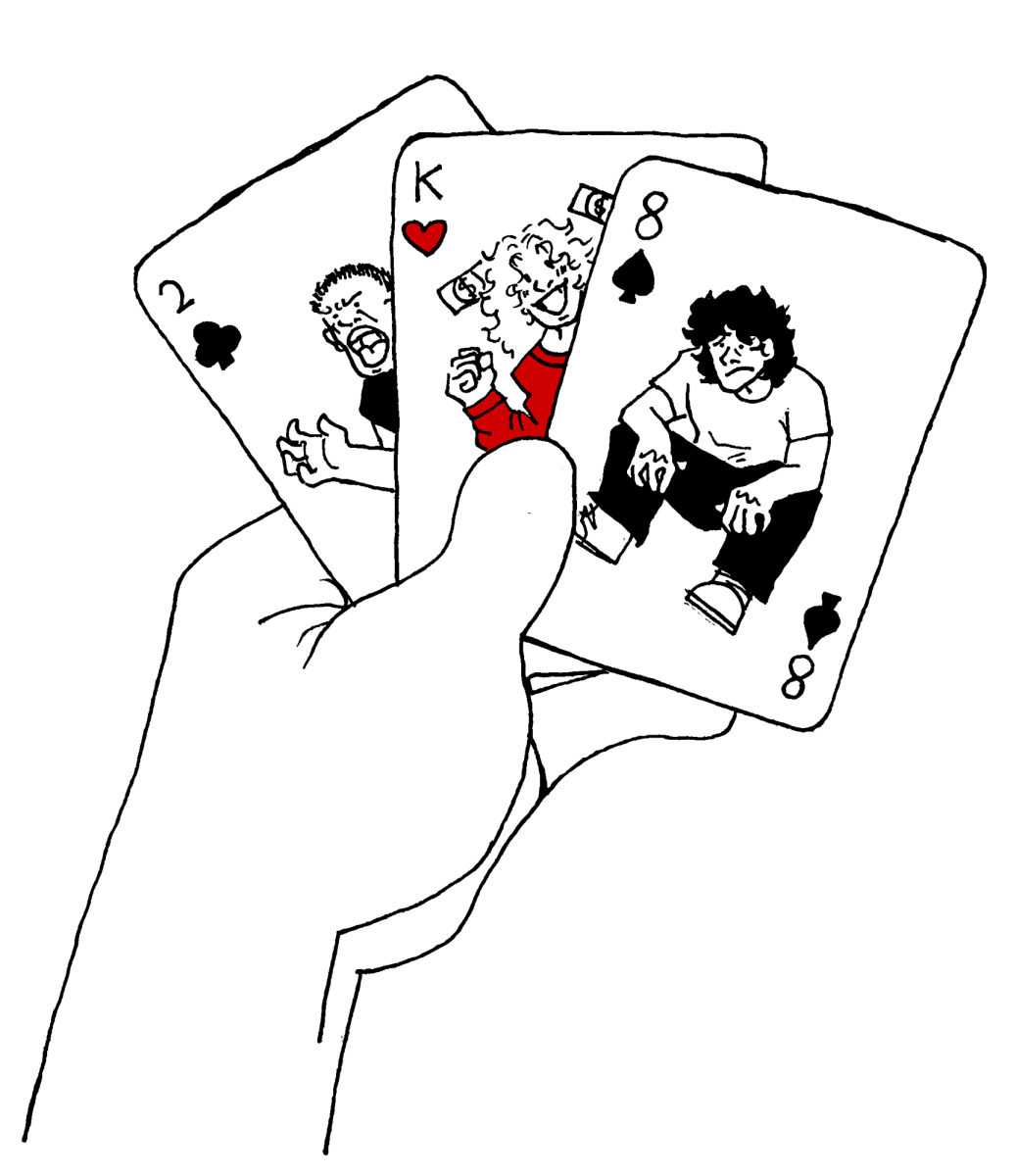

“Boyhood”, directed by Linklater, follows a young boy from early childhood to his first day of college. It’s grand in scope but maintains a close study of its many characters: a feat within itself.

Linklater uses a few tricks to develop a strong sense of relatability and nostalgia. For those who don’t already know, the movie was filmed using the same actors over the course of 12 years, and although it could have been a huge gimmick, it wasn’t. There’s always discomfort in accepting changes in actors, and it’s not present here. However, seeing characters grow up on screen isn’t what makes the movie great. It’s less the defining aspect and more a possible rough edge that’s been smoothed out.

Mason’s mom (Patricia Arquette) is essentially a stressed single mother with a poor taste and dangerous dependence on men. At first. Like every other character in the movie, she grows. By the end — single again — she’s a matriarch whose strength stems from an independence from men. Now imagine every character, main and supporting, each with their own natural arc.

But where does the supposed genius of “Boyhood” lie? What makes it something more than a solid flick with aging actors?

It’s buried, deep in the structure of the story. Linklater shows, in the two hours and forty five minute running time, very few key moments in Mason’s life. No first kiss, no eighteenth birthday. The audience won’t see Mason for a year, and suddenly he’s got a deep voice and a beer in his hand. Or his mom is married again. Or his sister is off to college. The list of implied events is long.

Don’t be worried. It sounds a little dizzying, to simply assume that all these changes happen. It isn’t, and here’s why: we, as functioning human beings, have imaginations. Mason’s first cup of beer, off screen, suddenly becomes your first cup of beer. It’s the melding process, how “Boyhood” connects you to Mason’s persona and captures your absolute attention. Not showing the important stuff is “Boyhood’s” genius.

“Boyhood” is a childhood captured and compressed to fit the big screen. You might not get memory loss like me, but at the very least, you’ll have an opportunity to reflect on what many call our best years.