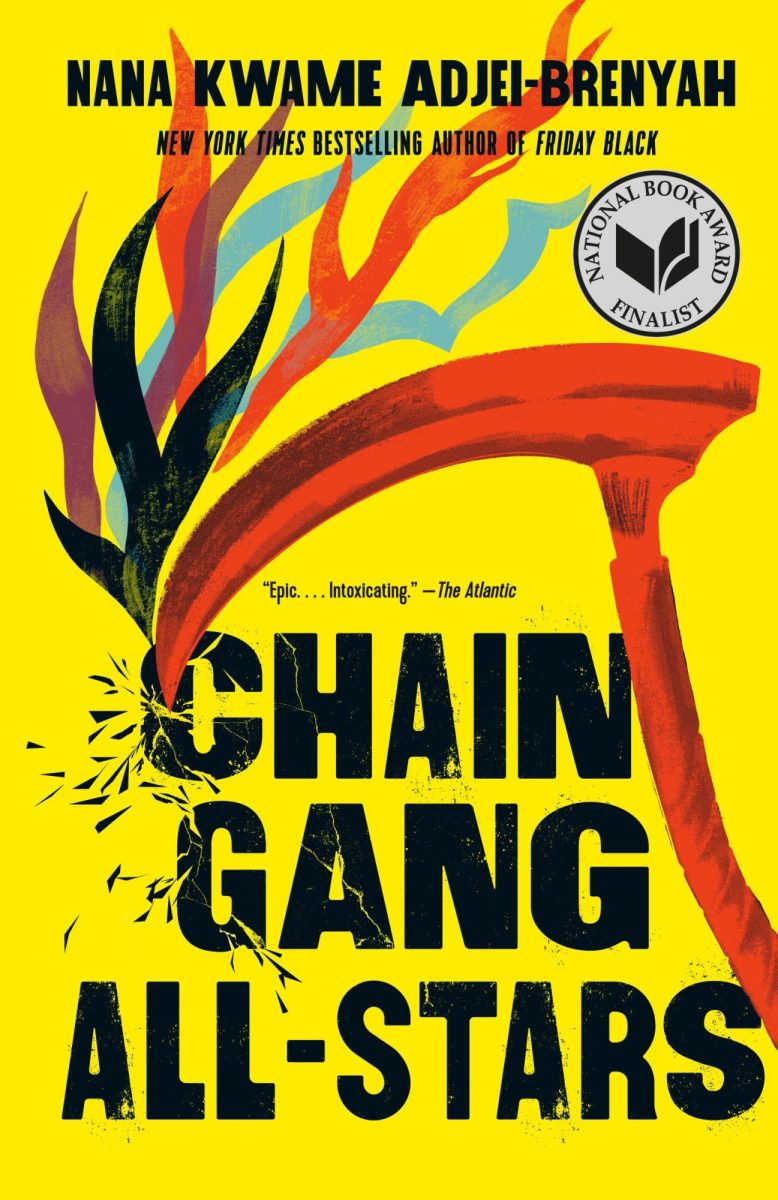

Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah’s first novel “Chain Gang All Stars” opens with blood. Under the electric lights of a repurposed football stadium, Loretta Thurwar makes her first kill on the “Circuit,” the professional scene of prison shanking. The America imagined in Brenyah’s novel is one brought to the brink of cruelty.

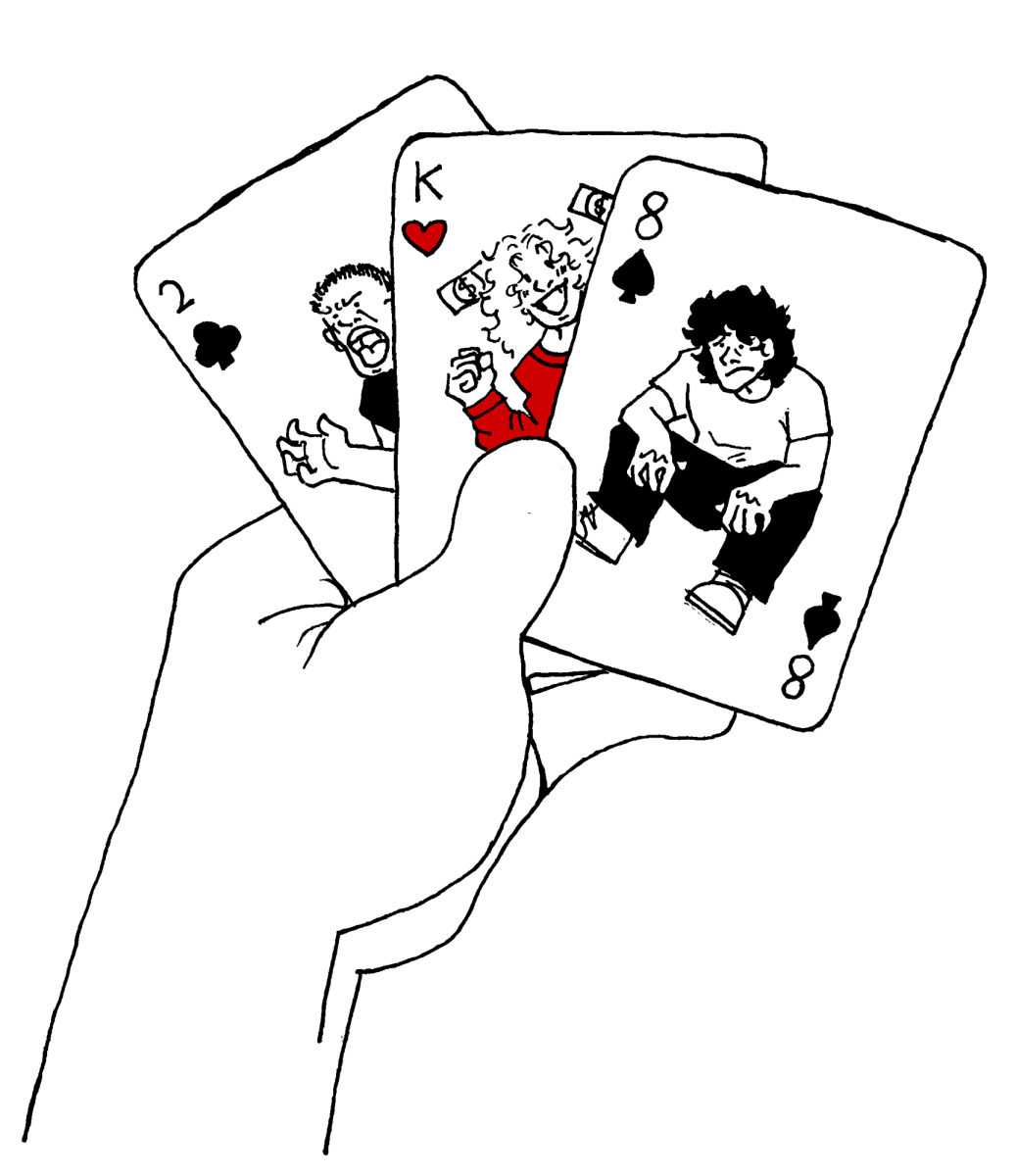

Prisoners doing life are offered a one-way ticket to early release, if, that is, they can kill. Incarcerated people on the reinvented chain-gang are forced to hunt each other for sport. Survive years, and countless deathmatches televised for millions of viewers, and you can be reintegrated into society. No one has ever done this. The life sentence doesn’t go away, instead the electric chair is replaced with the sharp end of a spear, or the blunt head of a makeshift hammer.

In “Chain Gang All Stars,” state-sponsored murder is recontextualized as sport. People are brought into the Circuit as murderers, whether from a bar night gone wrong or a relationship souring at the worst time, and if they manage to come out the other side it will be as serial killers, all to the thunderous applause of American sports fans.

In the second deathmatch Adjei-Brenyah details, Hamarah “Hurricane” Stacker lets her scythe eviscerate her opponent. Before the blood has started to dry the crowd is swooning. For so many people, the lines between entertainment, justice, and death have blurred into unrecognizability. There is no remorse for the Links fighting on the Circuit; the separation that their prison sentences lend to the rest of society means that they may as well be links on a chain. Or, once Thurwar’s hammer, nicknamed “Hass Omaha” reaches them, just blood on a football field.

Starting this July, at the Angola Penitentiary in Louisiana, a front row seat for the same kind of carnage is just $20. Another season in the 60-year long tradition of Angola’s “prison rodeos,” the draw that brings in thousands of attendees every year is the gore. At Angola, incarcerated people are offered a chance at propping up the almost nonexistent salary they receive from working the fields, with prizes for the various games being enough to afford even a phone call home.

The games all center around one theme: inmates risking their lives, usually in front of the gleaming horns of a massive bull, to beat out other incarcerated people for a grand prize. Playing “Convict Poker,” participants attempt to hold onto a table for as long as possible while a bull runs them down. In the signature event, “Guts and Glory,” prisoners serving sentences from life to misdemeanors grasp for a poker chip strapped to the bull’s forehead. As the front page of the official website for the rodeo, angolarodeo.com, asserts, “Welcome to the wildest show in the South!”

Children as young as two years old sit on their parents laps as they cheer on the show. The rodeos turn a profit, with the venue holding up to ten thousand watchers all eager to buy local Louisiana food, and stare rapt at one of Louisiana’s biggest injustices.

Lara Naughton, writer for the paper “Guernica,” says in her article on visiting the rodeo, “America’s Prison Rodeo: In Louisiana, incarceration is a spectator sport,” that “The grand event of the day was Guts and Glory, in which a poker chip was tied to the forehead of a wild Brahma bull.

Contestants tried to get right up to the bull in order to grab the chip from between its horns. It was mayhem in the ring and an explosion of cheers in the stands. I don’t know how many contestants were injured but I saw one bloodied man carried by two EMS workers to the ambulance that was stationed on the other side of the fence.”

For the incarcerated individuals inside Angola, the prison rodeos represent a chance for a taste of freedom. For the viewers packing the stands, they’re entertainment.

In Adjei-Brenyah’s “Chain Gang All Stars,” the near future he describes, warped by prison labor as sport, doesn’t look that far off. The plot mirrors the reality of incarcerated people in the real world, reduced to a spectacle, their lives, according to thousands of Americans, holding less weight the second they cross the entrance to a penitentiary.

Towards the end of the book, people install “holoscreens” in their houses, floor-to-ceiling televisions designed specifically for viewership of the death games, American’s apathy making its way into their hearts and their living rooms. On the other side of the coin, though, this plot beat says something else: we must be aware of injustice before we can fight it.

For the wife of a Chain-Gang superfan, the holoscreen becomes a window into the brutality she wasn’t otherwise conscious of. In the same way, Adjei-Brenyah, his writing bleak and oppressively cynical, rips the mask off of American oppression towards its prisoners by paralleling his fiction with Angola’s all-too-real prison rodeos.