It’s a universal truth that audiences are more apt care about social or political issues when they’re presented through a colorful narrative. Or perhaps political commentary is just more effective when it is also beautiful art?

Regardless of medium, I do think it’s true that people better recognize a pattern of oppression when the setting is unfamiliar: a story of cultural erasure taken out of the context of human life. Although, with the addition of giant, blue, humanoid aliens in this film, there are also people.

For an adult animated movie that received little mainstream attention upon its 1973 release, it’s nonetheless easy to see why ‘Le Planète Sauvage’ or ‘Fantastic Planet’ has remained a cult classic.

Created by René Laloux and Roland Topor, the French-Czechoslovakian film reflects the political upheaval of its time. As “Fantastic Planet” was animated with the help of a team from Prague, production was halted periodically in the heat of the impending Soviet invasion.

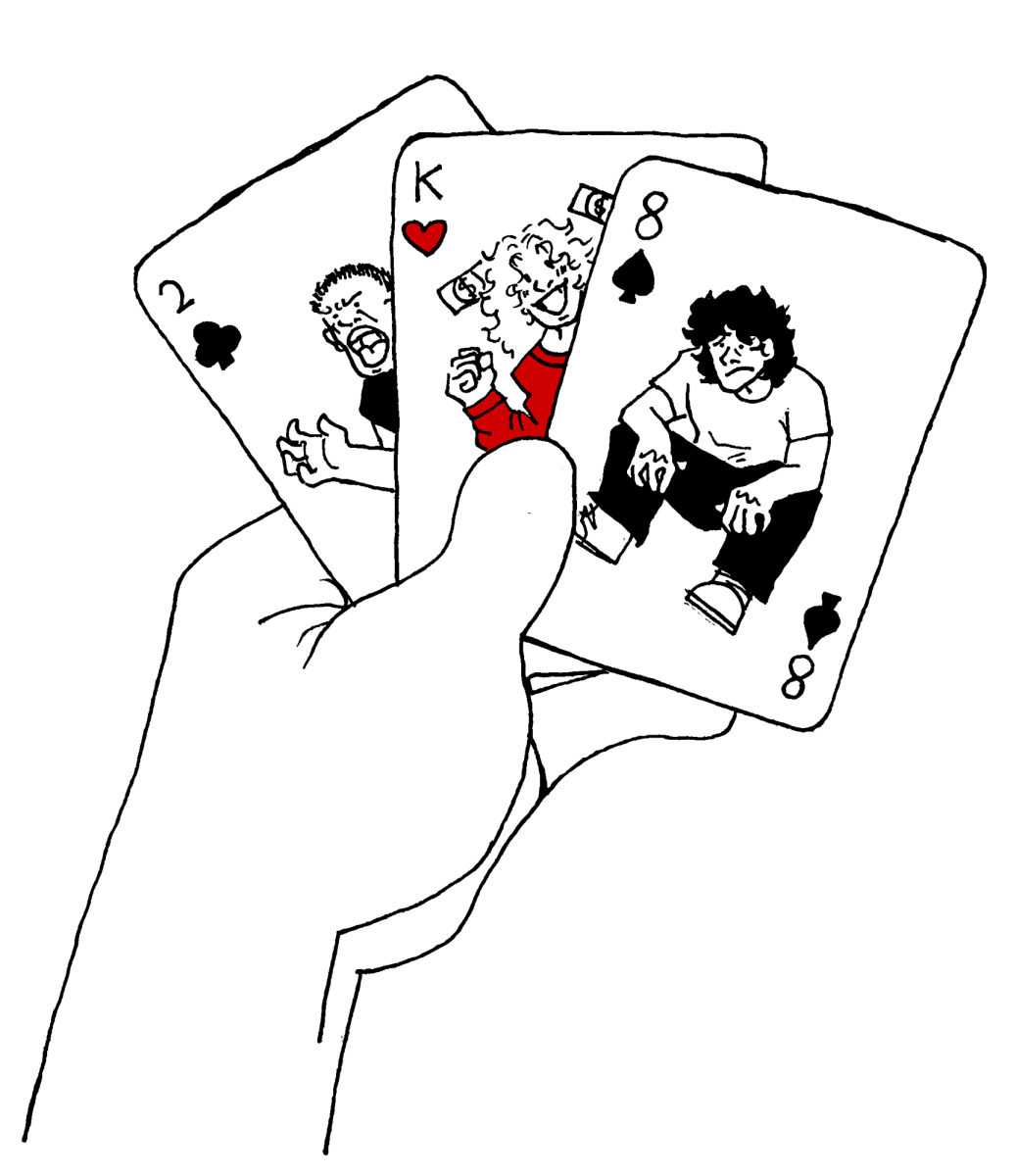

As for the film’s bones and aquatic gills, “Fantastic Planet” follows the shaky coexistence of two races on the planet Ygam. After disaster causes the human “Oms” (a homophone of the French word for men) to leave their home planet, a species of highly spiritually and technologically advanced aliens called “Draags” begins the enslavement and attempted extermination on the much smaller creatures.

This imbalance of power and perceived superiority of Draags is both physical and intellectual: the blue, red-eyed dominant race towers above Oms, their practices of meditation and advanced structures are easily visible amid a sparse wasteland populated by wild, surrealist-animated animals and Om colonies.

Established as adversaries, the only time the two main species interact is through the extermination or domestication of Oms. Just as nonhuman animals are treated on Earth (a commentary made clear throughout the film) the small creatures are either pets or pests, played with and coveted when convenient, but eliminated when their intelligence is seen as a threat to Draag dominance.

However, beyond the trippy animated landscape of foreign creatures that make “Fantastic Planet” seem authentically otherworldly, are the very Earthly dynamics between the oppressors and oppressed.

When the film’s protagonist “Ter” –-a name audibly indistinguishable from the French word for Earth –escapes his captors and brings his Draag knowledge an Om colony; the “wild Oms” shame his pet-like domesticity.

The film in this aspect clearly captures the isolationist nature of in discrimination: these separate colonies of tiny humans, although sharing a common enemy, discriminate against the formerly domesticated and do not unite until prompted with escalating violence.

“Fantastic Planet” manages to conclude cleanly, the two races recognizing their differences and eliminating thoughts of genocide on the part of Draags. An artificial planet is created on which Oms can live. Posing a peaceful, yet slightly Earth-irrational solution to end their problems of irreparable difference.