In the 2023 film “Everything Everywhere All at Once,” there’s a poignantly silent scene between two rocks, standing still as their silence is translated into subtitles above them, about how discoveries about universes have made humans go crazy. One quote rings true in the soundless abyss: “Every discovery is just a reminder — We’re all small and stupid.”

As science progresses exponentially, the stream of knowledge we have about ourselves, our planet, our galaxy and our universe has continually expanded; a small infinite point of mass exploded and created the elements, the stars and, eventually, us. We truly are all made of stardust.

These facts, that seem rushing toward us daily on our violent phones, paralyze us with fear over the knowledge that our lives, our existence, has been growing smaller as the universe becomes larger.

Humanity started with the idea we were at the center of everything, that some divine being centered us in our own personal oasis. While questions of theology have evolved through the centuries, we have come to understand that we are not the center of the universe: we’re not even the center of our own galaxy. The center of our galaxy, the Milky Way, is the Sun, which we are three planets away from.

We have discovered when the Sun will die, when our planet will be swallowed by its fiery maw, we have sent people to space, to our orbiting moon and on the edges of Earth’s atmosphere, and we have made it our mission societally to abandon our planet for a newer one.

As our planet slowly becomes dilapidated by climate change, as the skies burn and the seas rise, we have set our eyes onto the great unknown. This unknown which has begun to paralyze us with the idea that we are not the center of our own lives, of our own planet, of our own galaxy, of our own universe.

There are already eight billion people living on Earth, spread across seven continents and seven seas, and yet we live singular lives: I think what I think, you think what you think. Singular lives, averaging at just about 80 measly years; 80 rotations around our Sun.

We think of this, what a year means to us, and then we’re thrown staggering statistics and data: “The Sun will die in five to seven billion years,” “The creation of the universe occurred 13.8 billion years ago.” Time that dilutes the significance of our lives, that undercuts the magnitude of our souls, of our experiences and of our time.

Increasing knowledge about outer space has opened space in our hearts to become alienated from what we truly should be evolving our understanding of what truly matters: ourselves. Increasing knowledge about the mechanics of humans, our souls and bodies, as well as Earth is by far a better expenditure of our time that pondering the mechanics of the unknowable universe.

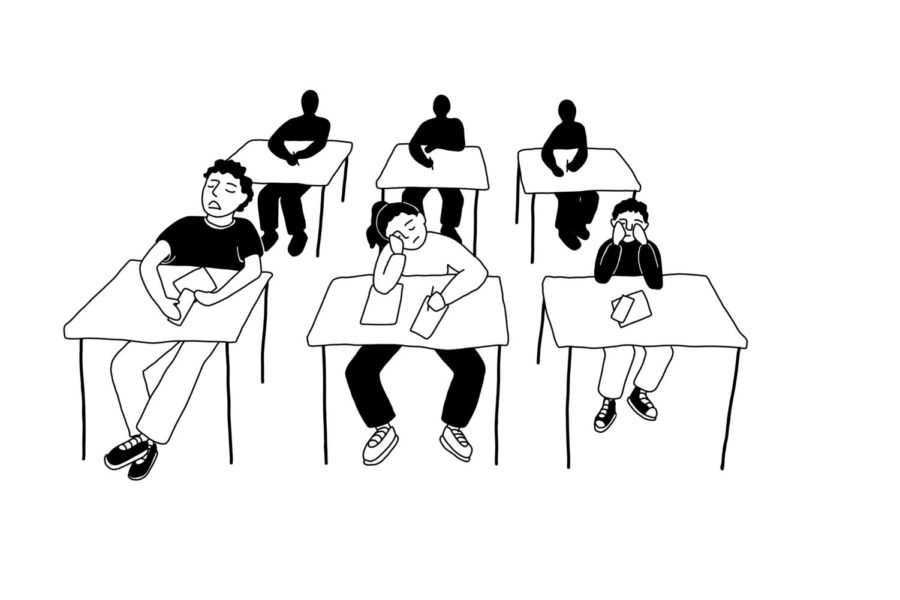

This sentiment becomes exacerbated as a highschooler, as a student. We are all on the cusp: we’re on the cusp of adulthood, of working, of higher education, of change. Being a teenager is the most confusing time to be alive, even without the looming thoughts of the unknown.

Already trying to make sense of our place in school, in society, in adulthood, how are we possibly supposed to make sense of our place on Earth, in the Milky Way, in the universe? The problem is that we aren’t; the existential ennui of being a highschooler is normalized to the point of disinterest.

However, taking the time to separate the labels society thrusts upon us, of seeing ourselves as “people,” can help us find purpose in an ultimately purposeless existence. There is no rule book to this endless universe, only our minds and our bodies.