The heavy, humid air was palpable, the sunlight even less avoidable, especially during its midday peak. Our fleet of minivans, each holding a handful of students, had the AC blasted and windows down, per our requests. All of us could only anticipate what adventures awaited us.

The Ecology Trip directed by Noam Gundle, a science teacher at Ballard High School took curious students like myself to Maui. Partnered up with Trevor Holmgren, world and American history teacher, they pioneered the 2025 Maui trip into an unforgettable experience.

34 total students took part in this scientific and cultural immersion; the group’s majority consisted of seniors and juniors, with sophomores making up the rest. Six more chaperones accompanied Holmgren and Gundle; some of whom had participated in the previous Ecology trip in 2023.

Our camp in Olowalu was situated on the western end of the island. Six cabins sat in a semicircle on the farther edge of our campsite opposite from the mess hall. Four of which were designated as girls only with the other two housing all of the boys. The assigned cabins seemed like a downside at first; I didn’t get bunked with anyone I immediately knew. After the first night, however, I was grateful for the randomization: I met some amazing people I never would have been close with otherwise.

Behind the cabins was a small beach with one sturdy, winding tree a few people set up hammocks in. If I stared out into the ocean for long enough, sometimes I would catch the spout of a Humpback Whale farther out. The cabins were roomy enough and all funneled into one boys and one girls bathroom with a shared outdoor shower and hose.

“It’s kind of just beds in the cabins so you’re forced to be outside, which looking back, I really enjoyed,” junior Lake Neill said.

Neill originally heard of the Maui trip from a friend that took part in the previous trip. After taking AP environmental science his freshman year the Ecology trip looked more than inviting.

“Oceanography in particular isn’t really of interest to me but I really loved the idea of getting into studying ecosystems…in a place so different from Seattle,” Niell said.

The Maui trip wasn’t only an eye opening experience to Neill.

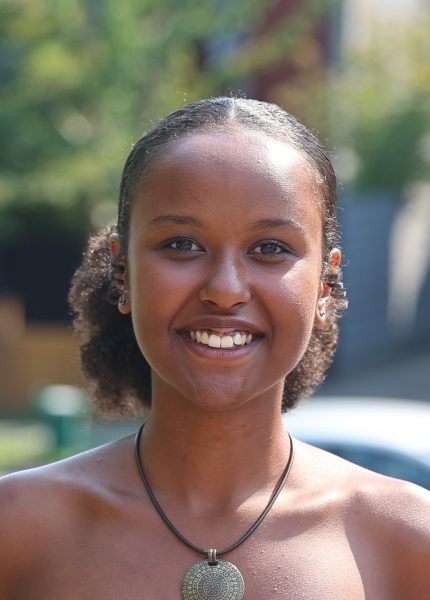

“I have an interest in potentially joining the maritime academy,” junior Mikayla Sullivan said. “I wouldn’t have been interested or known about the Maritime Academy without the trip.”

I personally didn’t have much interest in the science portion or the trip though it was incredibly informative. The cultural aspects were more of my focus: Thankfully, as Gundle said, “We did that more this year than previous years.”

To earn the science credit students are required to conduct ecological observations and produce a research project on their chosen subject.

“We’ve been trying to make it less of a focus because we don’t want students to get overwhelmed by it,” Gundle said. ”…that’s why we are always trying to give students free choice and allow them to pursue their own educational goals.

Each student was mentored by one of the scientists on the trip; I was matched with Gundle and he helped me hone my focuses into something credit worthy.

Gundle recalls his initial love for field trips starting in his high school career at Garfield. His former science teacher, the late Craig Macgowan, pioneered the first ecology trip to Maui and became a mentor for Gundle and his later teaching career.

“I always walk in the footsteps of those who came before me,” Gundle said.

Those footsteps are what led him to make his own changes to the program and introduce it to Ballard.

“I came as a chaperone on the Garfield trip in 2012 and I looked at; what are they doing that I love? What are they doing that I don’t love,” Gundle said.

Aspects like the cook crew-which rotated everyday- included; one group of students responsible for breakfast, lunch and dinner were details taken from the 2012 Garfield trip. Talk story was a similar token of inspiration; the group responsible for the cook crew the next day would recount the day’s activities and draw them to be presented at dinner. Their presentation included the plan for the following day and the “word of the day.” One that stuck with me was “laulima” which was defined by the non profit organization Kipuku Olowalu we volunteered for as “many hands make light work.” This Hawaiian word was common between many of the organizations we came into contact with and was regularly paired with “ohana” which means “family.”

We were all one Ohana in Maui and many of those people I bunked or ate dinner with I stay in contact with today.

“Ohana means family and the way we work together on this trip is we depend on one another,” Gundle said.

Mikayla • Apr 4, 2025 at 4:10 pm

BEAUTIFUL!! Reading this brought back memories of the trip and how I’ll always hold it very close to my heart for the years to come. Great job Abby .