There’s so much glamor in this world: glamour covered by thick clouds of smog that clog skies, seas, cellular devices and the scenery of life. It’s a struggle trying to find the beauty in what appears to be such an ugly world, especially when there is an emerging discourse online debating whether or not beauty even exists in the face of war and death. But what is life if not the exploration of meaning, and what is meaning if not beauty?

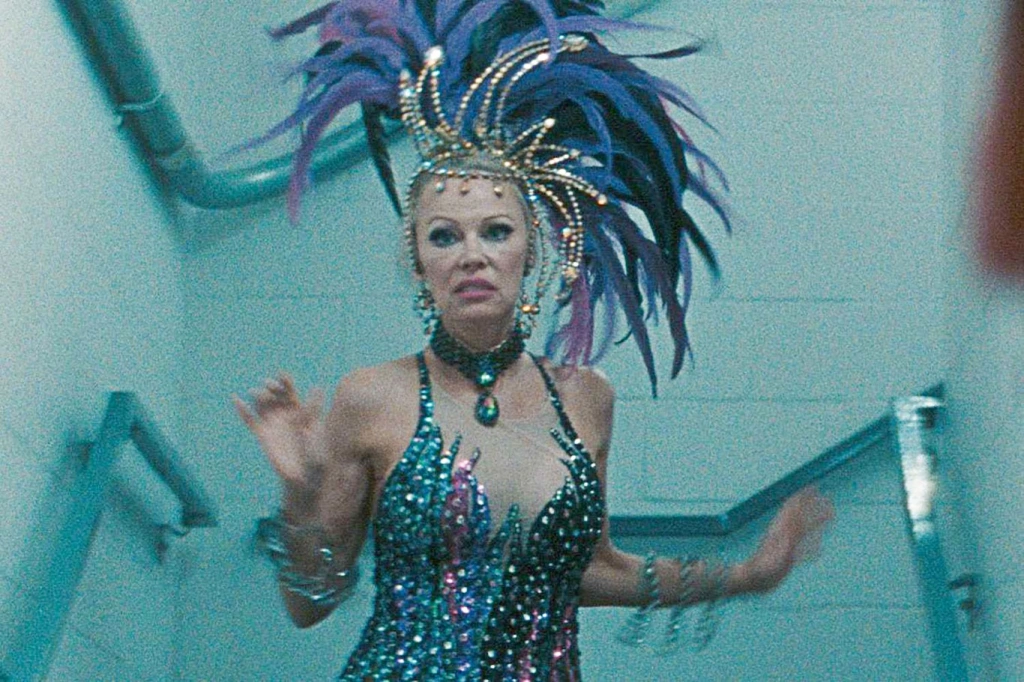

Luckily enough, Gia Coppola’s “The Last Showgirl” gives us a character who is intrinsically tied to what she conceives as beauty; Pamela Anderson plays Shelly, a 57-year-old dancer who has led a 30-year run as a Las Vegas showgirl. Shelly is desperately naive in a desolate world, her constant diatribes of “the Las Vegas showgirl” cloaked in musings on the “costumes, the sets.” She considers herself, and her fellow dancers, “ambassadors of style and grace,” something she desperately clings to as the movie progresses.

She is forced to reckon with this idea when she is told that her show, “Le Razzle Dazzles,” has been cut and there are only two more weeks left of the show. In her grief and trepidation, she is surrounded by her fellow dancers, mainly Annette (Jamie Lee Curtis), Jodie (Kiernan Shipka) and Marianne (Brenda Song), all of whom offer varying degrees of interest in dance.

Annette has quit the show for seven years, instead working as a waitress for a casino, Marianne abhors the show and views it just as a job, while Jodie, the youngest, has more modern ideas about dance and entertainment. All of them offer a stark contrast to Shelly, who is often deluded about the importance of dance, as well as her own abilities and skill.

Such a glamorous movie indeed this is: only clocking in at around an hour and a half, Gia Coppola revels in the short time by offering equal bits of peace and dysfunction. Beautiful yet blurry shots of Shelly or Annette are common, their quiet contemplation juxtaposed with the soaring Las Vegas monuments. The cinematography, done by Autumn Durald Arkapaw, is achingly nostalgic, Shelly’s own adoration of the past evident in the attention played onto the rhinestones of her costume and the makeup caked on her face.

However, the script itself falters: a good deal of it ruminates on Shelly’s nostalgia, with Shelly being given these disjointed and out of place lines of the time. In an opening scene, when asked if she has music she turns and says that she “gave it to the maestro.” Oddly jarring at first, these eccentrics in the script are luckily only prevalent in Shelly’s lines, which does more to show her love of the past than the dysfunction in the script.

Pamela Anderson’s performance gives these lines some depth and much needed reflection. Anderson does not reduce Shelly to a crazy woman lost to the past but instead someone mourning the attraction of her past self, in a world that admonishes the aging sentimentality of women.

As a woman previously cast aside as nothing more than a sex symbol, Anderson’s nuanced history gives needed context to Shelly and the audience’s interest in Shelly. Shelly is both an incarnation of Anderson and a dichotomy of her: she is someone reduced to her beauty but someone uninterested from lapsing herself from it.

In Shelly’s and Anderson’s performances, we as the audience are given a clear and unabashed look at someone so desperately craving beauty and reframing their vision to see it everywhere. Las Vegas has so much beauty in “The Last Showgirl,” with the showgirl, namely Shelly, being offered as its ambassador, ready to impress glamour upon us unglamorous people, in an unglamorous world.