We, in America, are regularly regarded as a “melting pot”: one homogenous culture composed of various, diluted traditions, personal beliefs and historical artifacts. All of these ingredients come together to form the “American identity,” one without a set place of origin but rather an intoxicating concoction of many.

A term that was introduced to me that I find much more fitting is a “salad bowl” mentality towards being “American.” Every flavor is unique, yet distinguishable; only enhanced rather than diluted by one another. Every “American identity” follows its own parameters, reimagining its definition to fit their traditional practices.

The dressing is the underlying title of “American” but every fruit, grain and leafy green still contributes to its individuality.

How is diversity even defined? What are the criteria to set apart one culture from another? Is it beliefs, religious or otherwise? Is it diets; indigenous foods and agricultural practices? Or is it surface level: skin color.

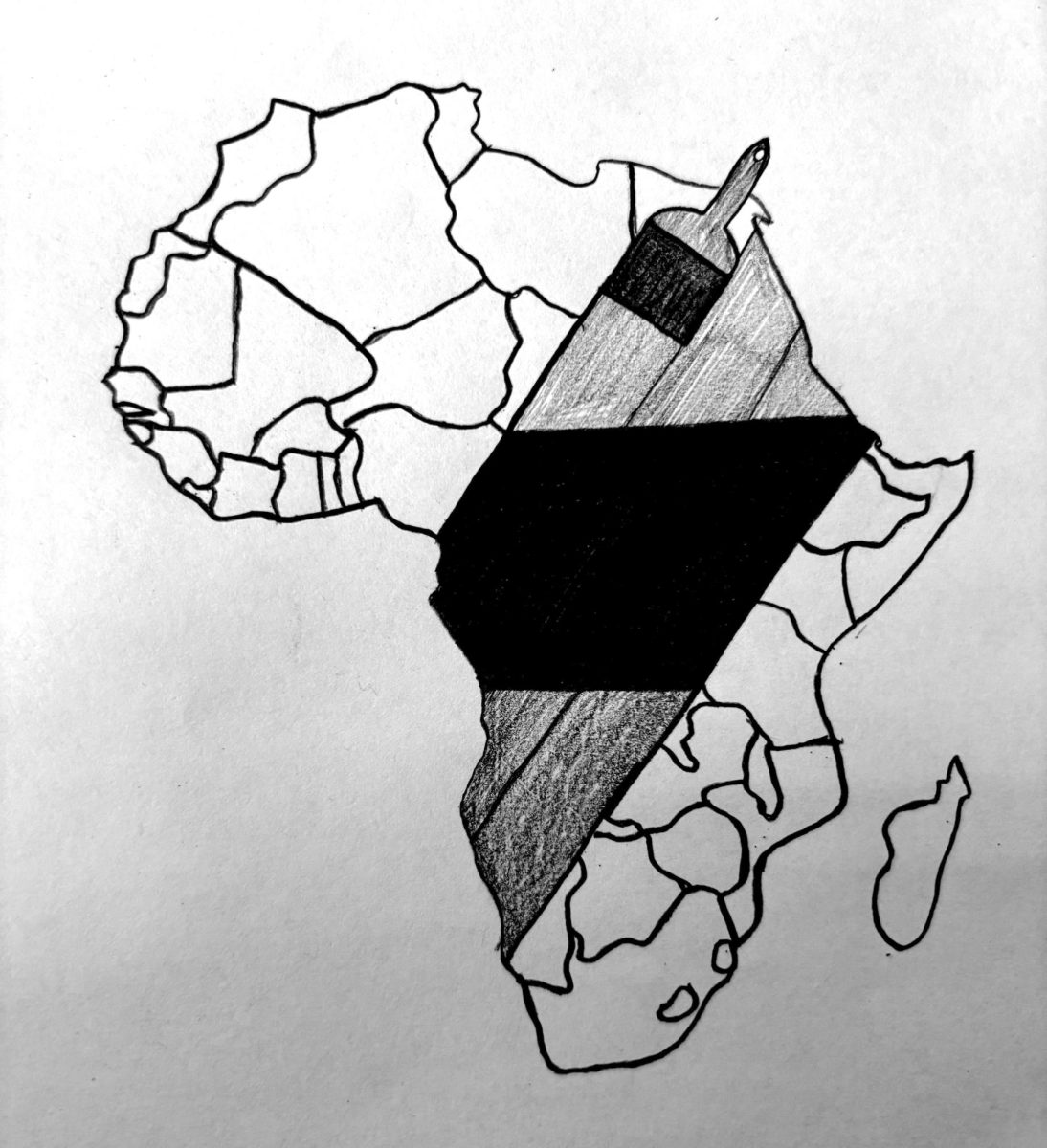

Wouldn’t that explain a lot? Africa isn’t even considered a melting pot; too few cultures are recognized to form a cohesive, homogenous whole. Instead, monolithic seems to be the preferred portrayal. I wonder why that is.

As a side note: I am sure many will have an issue with my drawn comparison of a country to a continent- I, myself, am not too thrilled about it. The difference in scales is vast, the multitude of people are greatly differing. However, I believe it is more beneficial to recognize these in relatable terms from perspectives that are personal and relevant. Finding parallels to such a foreign place to someone’s own hometown explains more than any statistic could. I do hope it is recognized that I work to connect this gained understanding to a more accurate scale.

North America is considered diverse on the basis of language – over 300 languages are spoken within the continent. Africa, on the other hand, contains over 3000.

Diet-wise, this trend continues. In mainstream media, Africans’ cuisines, plural, tend to be synonymous with fufu, a traditional Nigerian dish:

On weekends, I work selling Ethiopian food at local farmers’ markets: more than once I’ve had people ask me where they can find the best fufu.

The Ethiopian food I sell is only their staple cuisine, traditional to the Amhara, the ruling tribe. Other dishes include: chuko, a snacking item from the Oromo tribe made of roasted barley flour, spices and kibbeh- a traditional ghi and marqaa, a stiff porridge like dish complimented by hot red dipping sauces. Outside of Ethiopia, Cameroon is known for its plantain dishes like tapé tapé, twice fried and enjoyed with a spicy pepper sauce.

From the contrast between these two countries alone I find it baffling to generalize and disregard such multeity. It really is adjacent to comparing Japanese dishes to Indian ones; both are Asian countries, but each are clearly distinct.

A study published by the Washington Post explains “Africans are more genetically diverse than the inhabitants of the rest of the world combined…”. Studies and findings like these are the first steps towards recognizing Africans’ immense cultural wealth and genetic diversity.

To broaden the scale, it sounds ridiculous to describe Asia as one homogenous culture; the diets vary dramatically, traditions see little similarities and the dialects are region specific. This ties back to my previous question I have presented: what determines diversity? It’s impossible to unify these groups of people under one cultural banner so why is it so easy to do the same for Africans?

Non-whiteness is considered reason enough to unify, that’s why we have terms like “People of Color” or “ethnic minorities.” The shared history of oppression for many Africans is “supposed to be” the basis for community building and understanding. This, however, only labels the rich depths of Africans’ culture with its shallow oppressive history, failing to acknowledge much else.

To take a step back, what influenced this advocacy for the recognition of African diversity started off with my own experiences as both a Black person and an Ethiopian. Tracing back my lineage, it is not connected to slavery whatsoever, something shocking to an uncomfortable amount of people. My complexion seems to be synonymous with

this oppressive history; too many times, I have been expected to know “my own history” and too many times I have had to correct adults and peers on their ignorance. It is frankly disappointing but honestly, where was the education that was supposed to teach them otherwise?

Elsa • Apr 28, 2025 at 10:37 pm

Yess Abby this is so well written and interesting!