There are times, in my long-winded history as a reader, when I cannot help the pervasive urge to judge someone for what they’re reading, or inversely, what they’re not reading. Out of most who judge reading taste, my relative genre jumping has allowed me to sit warmly in my hilly house: I’ve read middle grade, fantasy, science fiction, literary fiction, thrillers, cozy mysteries, young adult, graphic novels, manga, classics, historical fiction and romance.

No matter the genre, this judgment is often unfounded, my own tastes obscuring any rational, or irrational, argument presented to me: to love a book is to constantly try and sell it. However, in my isolation from reading in the past year, a transition of reading 100 books a year to around 20, has allowed me to shed this needless judgment and read in peace.

Through a perfect storm of stress and increasing workload, reading has unfortunately been sidelined for more “important” tasks: working, studying, sleeping, scrolling.

I have not isolated myself from these realms of reading. My decreased appetite for fiction has not prevented me from watching dozens of people feed me their opinions on their favorites, least favorites, guilty pleasures, all of which seemed interesting to me no matter the degree of their opinions.

In this journey learning about the thoughts of others and not of the self, I noticed an acute divide in the factions of the literary glitterati: those who derive reading as a hobby of intellect and those who view it as a hobby of entertainment. According to these factions, Colleen Hoover is devoid of any intellectual meaning or she’s a champion of domestic abuse advocacy; Kant is either the greatest philosopher ever or the most boring author ever.

These two factions are incredibly interesting, especially as someone who reads for both amusement and knowledge. Two of my favorite books of the year are “The Tainted Cup” by Rober Jackson Bennett and “Convenience Store Woman” Sayaka Murata, both vastly different in plot and substance.

The former is a Sherlokian murder mystery set in an eco-fantasy that felt incredibly immersive and impressively twisted. The latter is a slice of life 200-page novel about the life of a 30 convenience store worker in Japan, broaching themes on the societal pressures Japan, and the world, put on women. My love for both of these books are valid, but there’s a different lens I had in reading these books.

There have been dozens of “pseudo-intellectual” books that I have stopped reading because I wanted something entertaining and dozens of “entertaining” books that I have stopped reading because I wanted something with “substance.” My own definitions for these words are also singular to my own reading experience: I do not find romance entertaining nor do I truly find historical fiction chock full of substance.

However, no matter my own personal boundaries of the fiction I read, a good deal of people can’t stop bickering with each other about their own boundaries.

Reading is already a dying art, the adage “print is dead” already haunting me well before someone placed a book in my hand, so why are we trivializing the merit of which people are reading? Is it on the basis of art or on the artist?

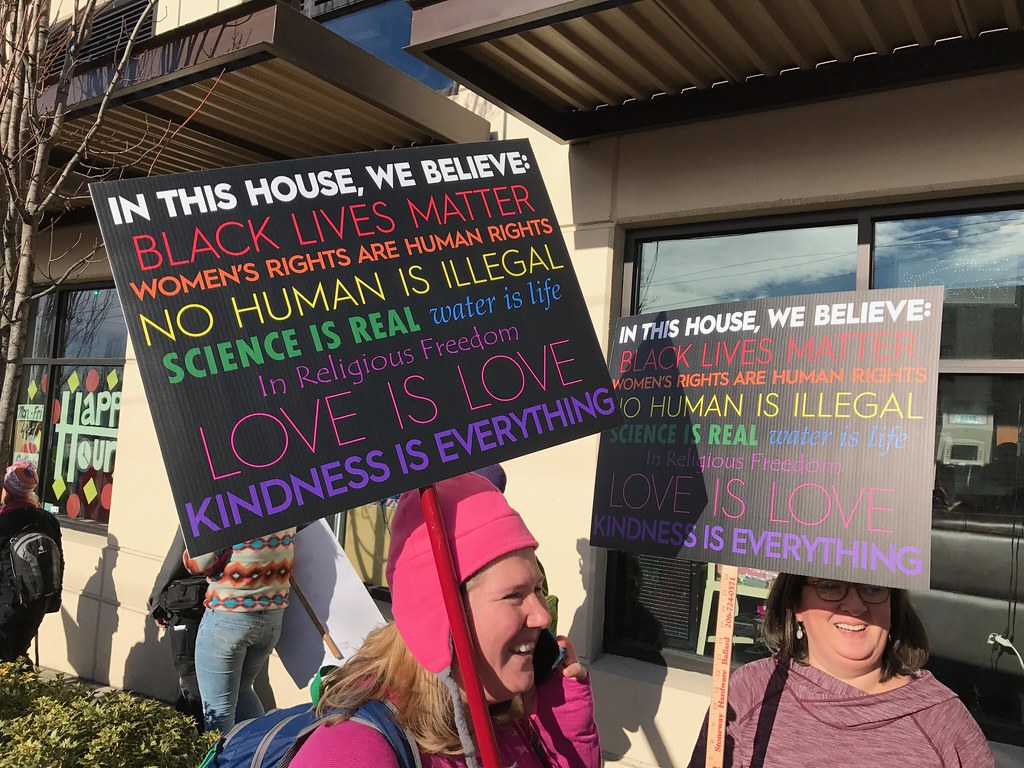

Many of the attacks lobbed from across enemy lines have been on the authors people are deciding to read: “Colleen Hoover romanticizes domestic abuse”; “Frank Herbert was homophobic”; “Sylvia Plath was racist”; “Sarah J. Maas is a plagiarizer”; “J.K. Rowling is transphobic.”

Splitting the artist from the art has become as tricky as splitting an atom; a whole mess of babble pouring out the minute the conversation bursts forth. There are dozens of nuances in this situation, the “right” and “wrong” blurry, but the way I judge and read a book is intrinsically influenced by the person writing it.

If a book is a fixed statue, unchanged after its publication, it can stand alone. But, its creator hangs around as its shadow, never forgotten in the context of the statue.

Whether or not we can split the art from the artist, do we have the capacity to split the audience from the art? The audience from the artist?

And then there’s quality: the actual writing of a book often comprises an argument on the reader. Is their validity in judging someone for reading, and enjoying, a poorly written book? It may be a doorstop for context; highlighting personal tastes, educational backgrounds, and a person’s relationship with reading.

Again, it often comes down to context. The “why” of why someone reads what they read influences my perception of them greatly: are they reading that book because it’s the first they saw in the bookstore? It was on the New York Times bestseller list? Someone recommended it to them? They like the author?

A twenty-something-year-old man reading Joan Didion or Eve Babitz holds different connotations than a woman reading the same books. (This own topic has sparked a conversation on performative reading: the practice of “reading” a book for social capital).

The reasons are endless compared to the lightning fast judgment we, and sometimes I, can make, not just centering the fiction someone dares to read. Judgment, however, can be a silent act.

So many people vomit their judgments onto the internet, onto their hungry audience, when, in reality, judgment can, and should, be silent under a layer of empathy. If someone name drops a book that won the Pulitzer Prize, is written by an author I love, is in first person or is a TV show, then I will hold their tastes, and subconsciously them, higher in my mind.

In retrospect, judgement is nonessential to the processes of reading, as my opinion holds microscopic pieces of value, though the power of a book and the perception it holds is intertwined with judgement/observations. Judgement may be irrelevant, but the ideological symbolism of a book’s cover and context greatly affects the perception many people work hard to develop, consciously or unconsciously.

![Being captain means a lot to Larson, having played basketball for his entire life. When asked about who their biggest competitor was going to be this season, Larson was very confident.

“[We have] No competitors,” Larson said.](https://ballardtalisman.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/brewster-color-1200x800.jpg)