Available one period, blocked the next, educators and students are forced to find ways around sudden restrictions of online materials. Appeal after appeal, teachers find it difficult to keep their curricula on track.

“I think it is inconsistent which is part of the frustration in that,” humanities and AP government teacher Kyle Morean said.

Not only is crucial information regularly blocked by Seattle Public Schools (SPS) but regulations and boundaries for what content will inevitably get blocked are unclear.

“We would like a clearer sense of what is available to us or just a heads-up this might be blocked on student computers,” Morean said.

A proposed solution has been to grant teachers the ability to view browsers with the same restrictions as students to prepare content accordingly. Whether this is a realistic or doable solution remains to be seen.

“Sps has shown a slow response when something that is needed for educational purposes, unblocking it,” U.S. and world history teacher Trevor Holmgren said.

The appeal process of an email to the district called a “tech ticket” to request the unblocking of certain materials. Responses from the district are mixed.

“Our response [from the district] for the past two or three years has been it’s our vendor deciding to block it and we’ll look into it with limited availability on unblocking those sites,” Holmgren said.

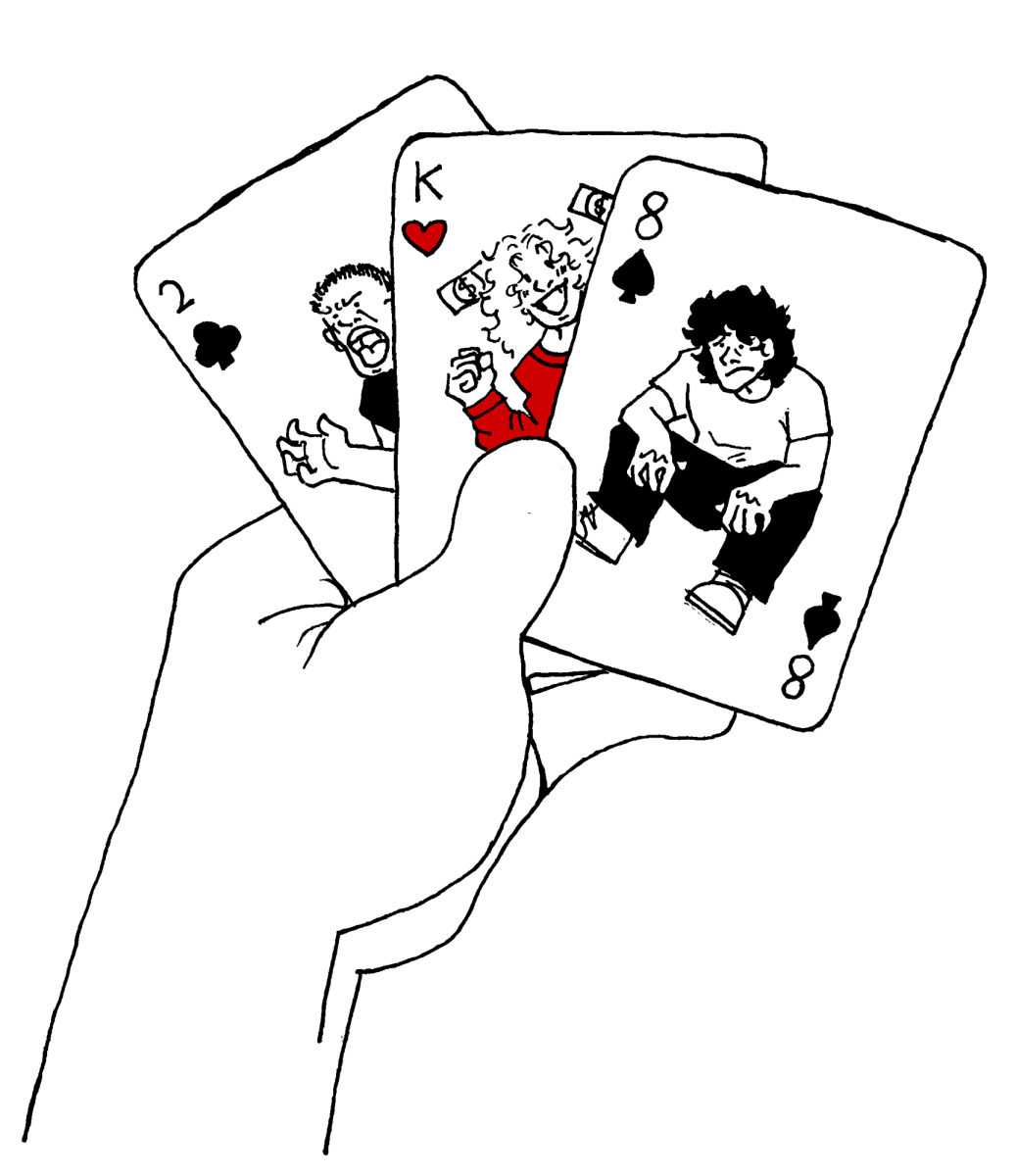

With unpredictable results and upended lessons, teachers struggle with providing in-depth curricula.

“And it [appeals] feels as though it falls on deaf ears,” Holmgren said.

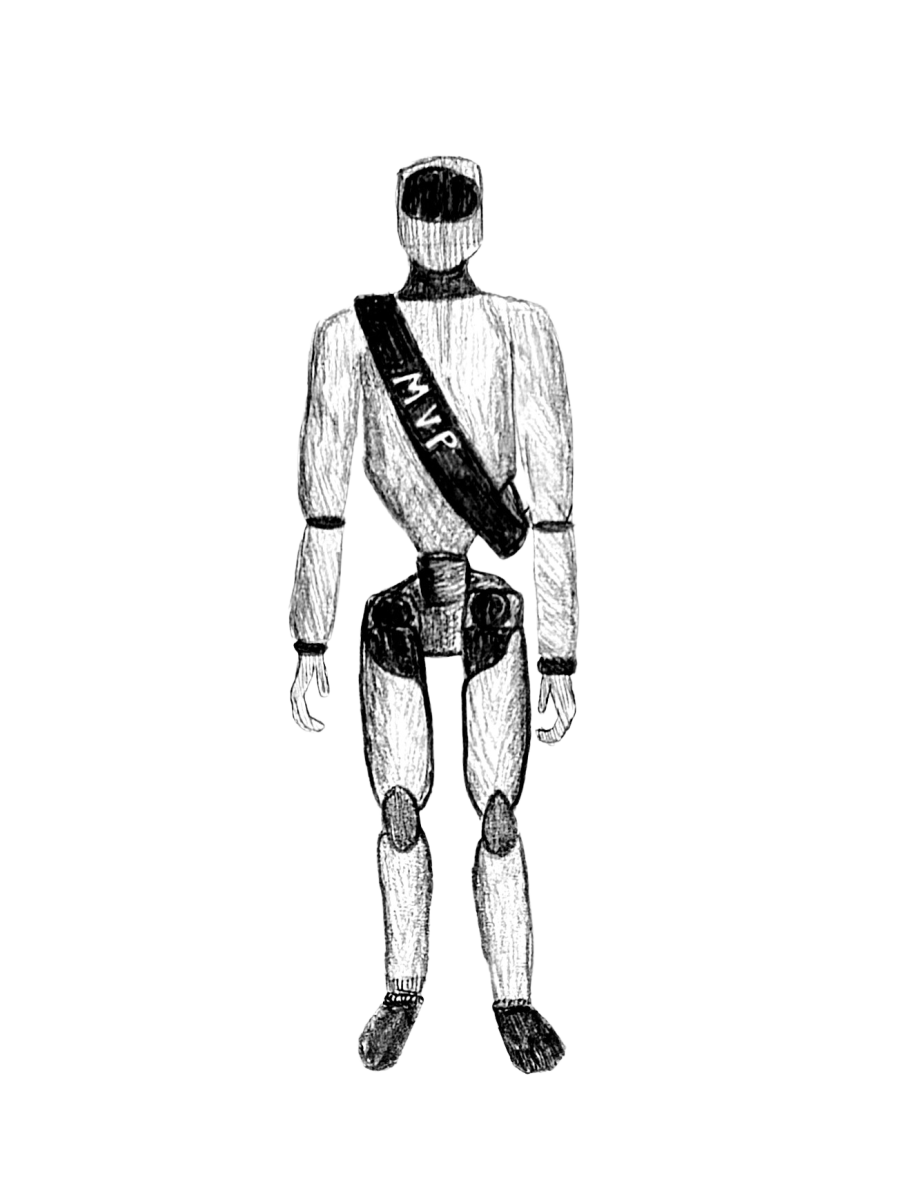

Software is largely to blame for these upheavals. AI algorithms are fed broad protocols that target both security concerns and teachers expertise.

“By painting with such a large brush around what is restricted, we cut teachers’ expertise out at the knees,” Morean said.

Holmgren shares similar sentiments: “It makes it really hard to provide specialty lessons for content when we are the content experts and people that are not content experts are blocking websites.”

Teachers continue to fight for the right to determine what content should be deemed appropriate for their own classrooms. Sweeping algorithms and slow communication prove to make that process burdensome.

“We are a district that likes to say that we care about social justice and ethnic studies and expanding the curriculum and I don’t know if we are actually doing that,” Morean said.

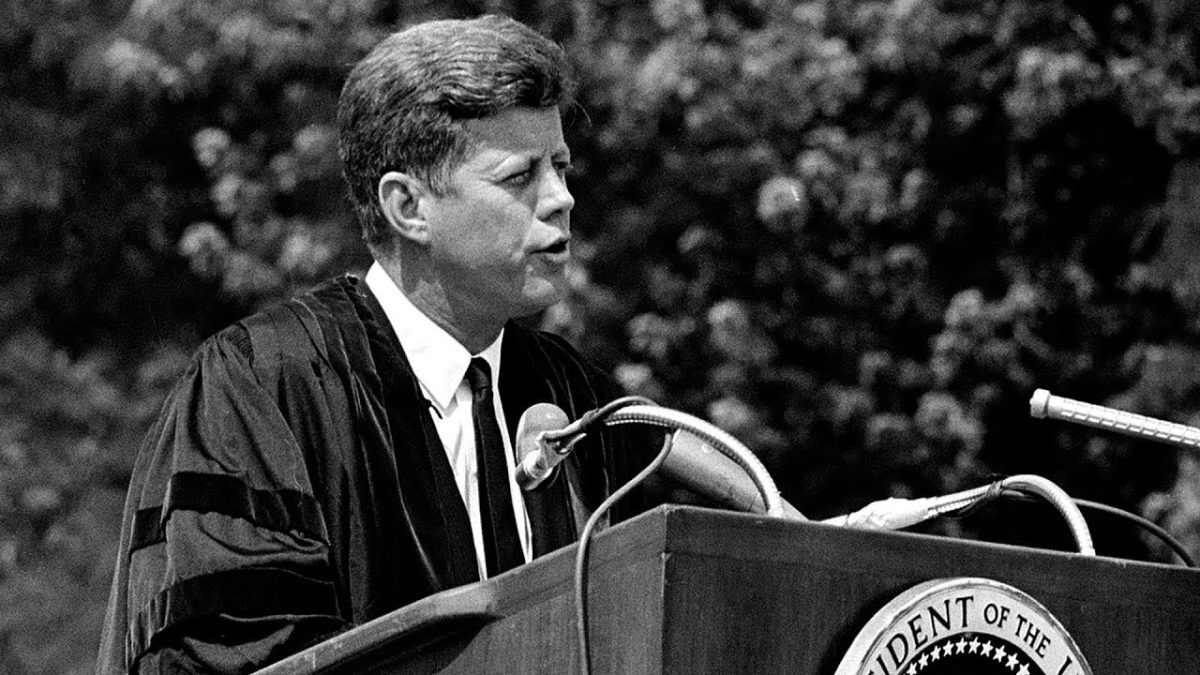

SPS restrictions tend to hit ethnic studies harder than other topics. Issues with Crash Course Black History have been noted along with any mentions of violence. Key terms like “negro” or “Holocaust” have been regularly blocked.

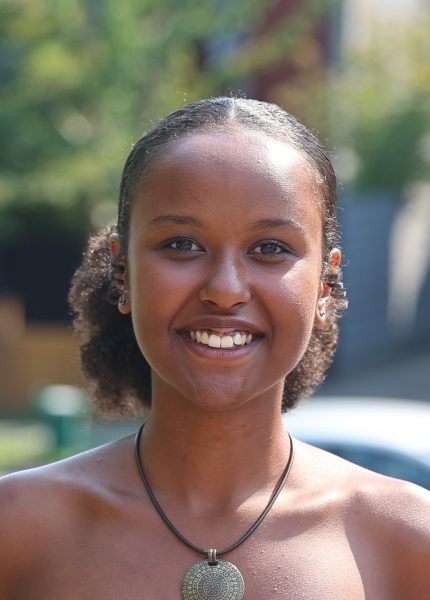

Both Holmgren and Morean recount the same story of how a student writing her junior paper on the portrayal of lesbians in the media found the term “lesbians” blocked for pornographic material.

“Practically, I’m more frustrated by the inconsistencies, ideologically I am more disappointed in the topics,” Morean said.

Holmgren points out that teachers need to find multiple online resources of already underrepresented content.

“If we are a district that says we care about perspectives that are not in our textbooks, then we have to be able to give teachers the latitude to fold in resources that might be mature content,” Morean said.

Teachers advocate for themselves and their students when they request more online freedom. As learning experts in their respective fields their goal is for students to have a well rounded education and perspective which is difficult with restricted learning opportunities.

The district does have the power to manually block websites; however April Mardock, the Cybersecurity Manager for SPS states that these are usually reserved for phishing or malware.

There is no review process for websites flagged by software, “we rely on teachers reporting issues to Techline,” Mardock said.

Teachers take the time to carefully vet sources for their lesson plans but when those links turn out to be restricted Holmgren describes the pains of providing less vetted content.

Comparatively, Morean said “I think from an issue of positionality is that if we want to have access to the resource then it is changing the focus and then putting it on me to deliver the contents to the class.”

Morean gives the example of Crash Course Black History, information provided by a Black American and vetted by a team of experts. When this resource became blocked fell on Morean to still provide that information on the fly.

“We get creative and trouble shoot where we have to,” Morean said.

Quick work arounds and last minute lesson plans are not unfamiliar to the teachers in SPS. Lack of communication between the district and schools and constant restrictions on crucial content leave students and teachers in the dark on the future of their curricula.