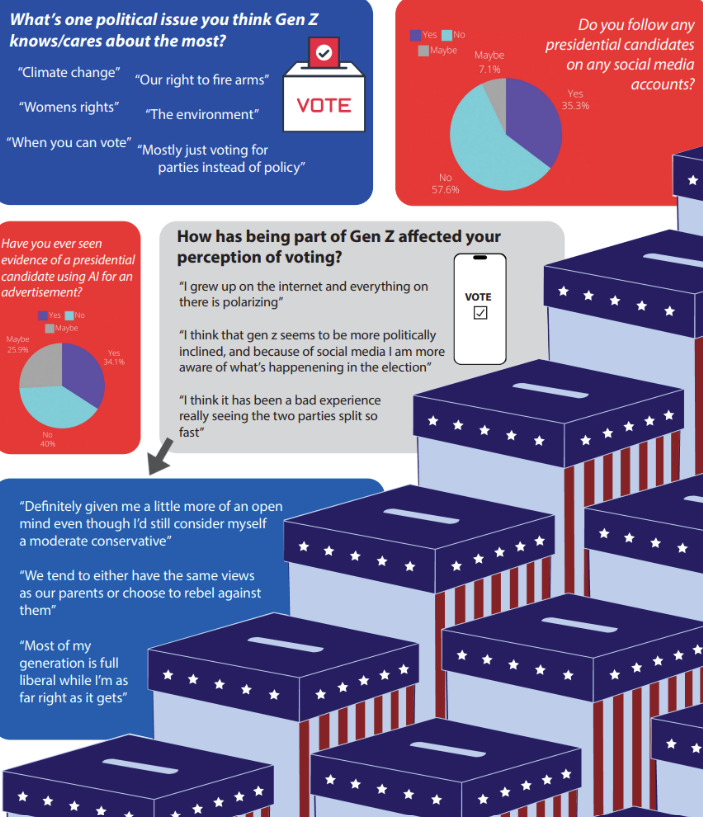

When it comes to social media use, whether it be for global news or light entertainment, political content seems to be the great generational connector. Serious or facetious, biased or impartial, the political landscape for people of all ages is defined by digital media. In fact, a recent Pew Research Center study found that 86 percent of Americans get their news online, making the upcoming presidential election vastly different from years past where campaigning is concerned.

But what does this mean for young voters, who are often the target of social-media centered campaigns? How is it impacting their willingness to engage in political discourse?

Ray Daughtrey, junior and humanities student, views social media as a complex force, as it has the ability to engage young people and display their preferred methods of dealing with conflict.

“I feel like [teenagers] don’t take a lot of things seriously,” Daughtrey said. “We’re so desensitized to the problems in the world and in our country that we just go on Instagram and make a big joke out of everything.”

The comical side of Generation Z (those born between 1996 and 2012), Daughtrey shared, is evident online. A.I.-generated images of former President Donald Trump wading through hurricane flood waters circulate as Vice President Kamala Harris is likened to Charli XCX’s electronica album “brat” as informal campaign promotion.

Polling from Gallup highlights that more voters may view Trump as a “strong leader,” though these statements may be based more around his gender than his policies, while Harris is viewed as a more “moral candidate.” Kamala HQ has utilized this tactic in the social media posts that it circulates, including the ones Davidson has seen.

“Harris is definitely appealing to younger people, where people haven’t in the past,” junior Rachel Davidson said. “Just having a TikTok page is reaching more people of our generation than other candidates.”

And while an adverse, comical reaction might make sense in response to seemingly insurmountable world issues, Kyle Morean, social studies and humanities teacher, worries this media may be directing our attention towards the wrong aspects of politics.

“I think [image] is unfortunately everything right now,” Morean said. “It’s been really telling that there isn’t much of a conversation around substantive policy.”

Although relying on image may be a prominent tactic for marketing, a candidate’s values still rest at the core of what some students claim they look for in a candidate.

“I definitely think that the way that they’re perceived is not as important as their policies and actions,” Daughtrey said. “I think I and other people I know care more about intentionality and what they want to do for our country.”

Some substantial political news can be found on places like Instagram, such as NPR posting updates of events with links to their long-form content. However, wading through the information – much of it carefully curated to catch our attention – can make it difficult to grasp important ideas.

“I think in the time since through COVID, we really saw an acute over saturation of information,” Morean said.

The sheer enormity of this content is another factor at play, as children and adults shift to navigate the world amid an influx of content and information.

“I feel like there’s so much to take in,” Daughtery said. “We have Instagram, we have TikTok, presenting us with all these things and we’re not really taught how to properly process that.”

Aside from social media’s ability to simply over inform, Morean, as a civics teacher, has noticed the impact of heightened social pressures and “cancel culture” on the behavior of his students.

“I worry that students are starting from a standpoint of, ‘I don’t know enough, and I’m worried that people aren’t going to like me if I speak up and say that thing,’” Morean said. “It’s the mindset of ‘I don’t want to offend, so I’m just not going to explore.”

Teaching the first and second half of Generation Z (and with much of his career taking place at BHS), Morean has developed an understanding of the way students in more liberal-leaning areas approach political issues: with both power and reluctance.

“I feel like I’ve seen the first half of Gen Z be more empowered politically with the sound bites they could get off of TikTok or Twitter, and that was kind of the hopeful rise of an impact I saw of social media spreading that political message,” Morean said. “But there is a closed mindedness around letting in other political opinions that makes me sad for the students who are more conservative leaning in our space, who don’t feel like they have any breath to take around this conversation.”

However, in Daughtrey’s opinion, a student’s willingness to speak up may depend on personal rather than environmental factors.

“It really depends on who they are,” Daughtrey said. “Because some conservative people are really vocal about that, and some just don’t want to share their political views.”

Daughtrey and Morean both argue, however, that the label of political parties often gets in the way of both informing one’s individual values and making an informed decision on voting.

“I really think that Republicans and Democrats, these two political parties, are so similar,” Daughtrey said. “There’s blue MAGA and red MAGA; We just gaslight ourselves into thinking, ‘yeah, if we go blue, we’re freaking fine,’ but do we even know any of Kamala’s policies?”

Similarly, there are some issues that don’t fit neatly into red or blue boxes, forcing the voter to either pick and choose their battles, or lean towards one side.

“We have been forced into these corners where, ‘if you’re not actively fighting the fight you are the problem,’” Morean said. “That is, to me, a really dangerous, binary, logic of discouraging people from being political independents and complex human beings that might have a policy issue over here and a couple policy issues over there.”

Despite the tendency to get caught up in bumper sticker labels, Daughtrey still holds pride in the shared identity of their peers. “I feel our generation is really open with what we think,” Daughtrey said. “We’re a really powerful generation.”

And despite the persuasive powers of social media, Morean is committed to creating a low stakes environment where students can develop their sociopolitical values without fear of judgment.

“Think, ‘how can you inform yourself, and assume the best of the person that you disagree with?’” Morean said. “Civics class should be a safe laboratory for those conversations to happen.”