There are moments when watching a film, when I feel as though the characters can feel the cameras on them; their struggles, hopes and fears dramatized and amplified. This division between audience and character can oftentimes feel predatorial, the audience consuming both popcorn and trauma.

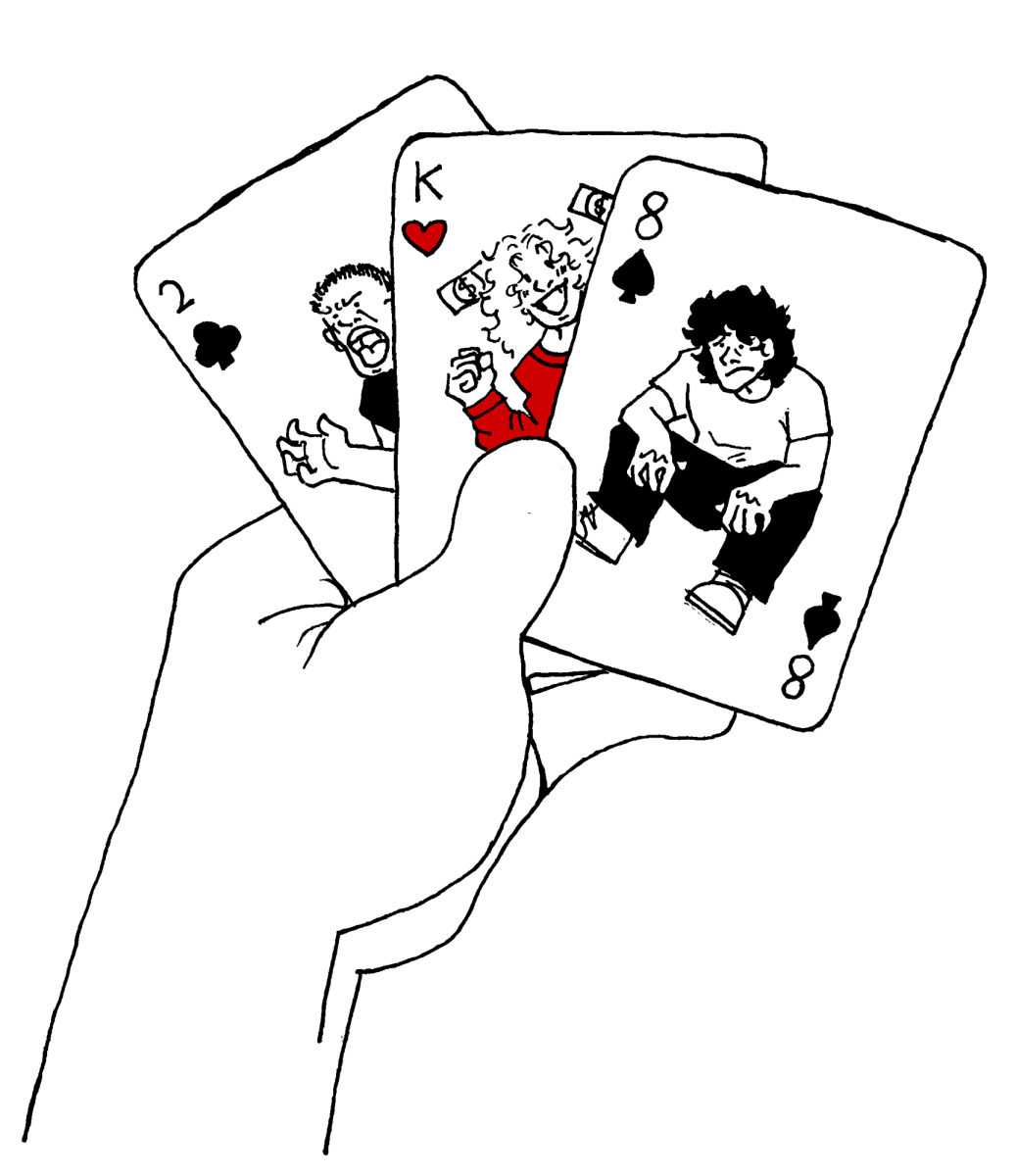

Luckily, in Azazel Jacobs’ “His Three Daughters,” Sisters Rachel (Natasha Lyonne), Katie (Carrie Coon) and Christina (Elizabeth Olsen) can barely emote in front of one another, let alone a theater of strangers, as they care for their dying father in his New York apartment.

This relationship is thirty years in the making, and Jacobs adds breadcrumbs of context to the messiness of it, even going as far as to start the movie with Katie monologuing at Rachel about moving away from their childhood squabbles.

However, old habits die hard as Katie hates Rachel’s weed smoke, the rotting apples in the fridge and Rachel’s inattention to the current situation: there’s as much tension in the air as there is the smell of marijuana.

The script is one of this movie’s biggest highlights, Jacobs, also the screenwriter, gives Katie and Christina grandiose and contemplative monologues that border on superfluous. Rachel is annexed from these long winded speeches, her dialogue muffled and curt in her sea of weed induced fatigue. Anytime Rachel is given a meaty piece of dialogue, it often carries more weight than the other two’s words, highlighting Natasha Lyonne’s performance over both Coon’s and Olsen’s.

One of the best shot and written scenes is simply a frank conversation between the sisters, pioneered by the peacemaker Christina, in which they collectively try to air grievances. Jacobs doesn’t use this opportunity to shoot for unrealistic standards, but instead gives his audience an unsatisfactory conclusion realistic to real life conversations.

It’s incredibly hard to be annoyed at these acts of realism, as they often give the characters a chance to act as reflective art pieces for human interaction: from Christina’s far off stare and the twitches of grief in Rachel’s eyes, what’s unsaid between the sisters offers a masterclass of showing not telling. A trait in movies that’s often overshadowed by the convoluted messes that are sequels, blockbusters and franchises. These movies have lost any semblance of subtlety, their meanings marketed heavily in a cloud of CGI and joke per minute dialogue.

“His Three Daughters” ultimately spends enough time focusing upon itself that it fails to cater to the insatiable appetite of modern media. Since Jacobs never makes his actors perform for their audience, he allows us to not be relegated to the role of “audience member:” we are just as important to the story as the actors.