Growing up, I was never “girly.” I wore my brother’s hand-me-downs and I hated Taylor Swift – I never felt the need to be feminine just because I identify as a girl. And similarly, pronouns were never a thing for me. Pronouns were just a part of speech that helped me identify someone without saying their name. It wasn’t until middle school that I started to learn that pronouns carry weight. That was when I started feeling a certain pressure to be feminine, to conform to my gender, to be girly.

By placing so much emphasis on pronouns, they have allowed for less binary distinctions of gender. Conversely, they are a piece of grammar that has gained influence over our identities – perhaps too much.

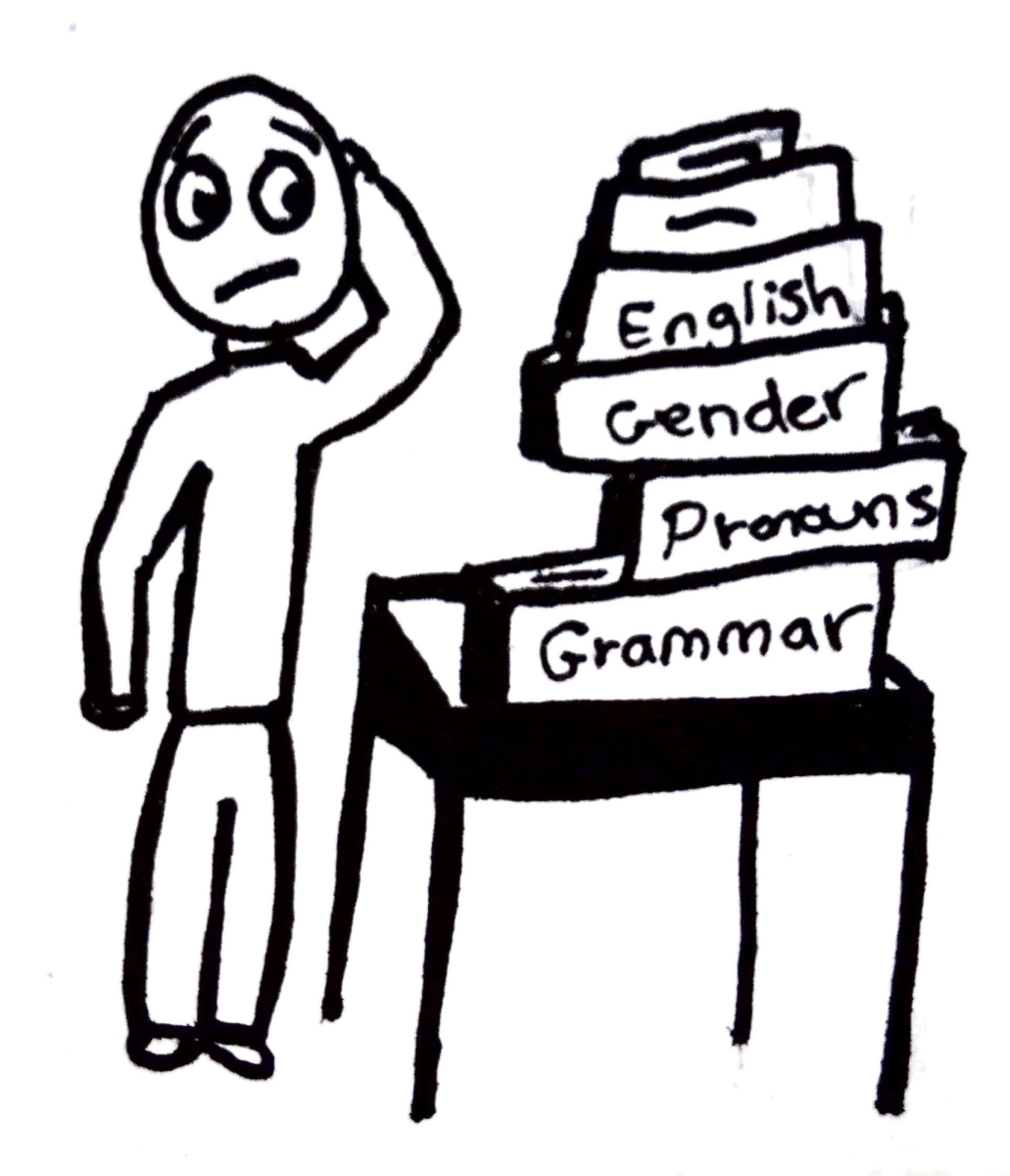

To preface, pronouns have had a complicated history in the English language. Even though it’s only started to become a prominent topic over the past few years, this history of pronouns has been far too overlooked for it to be so widely discussed today.

Given how little grammar is emphasized in American education, it is not surprising to hear that the English language technically has a missing pronoun – and that I have never second guessed its absence.

According to the New York Times, some languages have a genderless pronoun, like the pronoun “han” in Finnish, or are genderless entirely, like Turkish.

But English grammar doesn’t have this. There is a missing pronoun: a pronoun that refers to one person, with either their gender unknown, neutral or withheld. According to the novel “What’s Your Pronoun?” by Dennis Baron, hundreds of pronouns have been coined to fill in this blank for over 200 years. Things as abstract as “heesh,” which was coined in 1860, were invented to try to fill this gap in English grammar.

However, as Baron discusses in his novel, there was already another pronoun in the language that fit into this gap: they. For example, take the sentence, “Everyone forgets their passwords.” For us, “their” is a natural pronoun choice, but for a while, the country wrote off “they” because it was ungrammatical. But it sounded right, so why wasn’t it used?

It turns out that English pronouns have deeply misogynistic roots. Up until the 1970s’ feminist push to erase sexist language in writing, that blank was often filled with the generic “he,” as in “everyone forgets his passwords.” In grammar books dating back to 1549, “he” could be used as both a singular and plural pronoun. But there were major inconsistencies here, i.e., the fact that women could be criminals but not voters. “He” refers to both women and men under the penal code, but “he” refers to only men under the British voting Reform Act of 1832.

Thus, “he” had numerous social and grammatical flaws and needed a replacement. But with hundreds of words coined to fill in this gap, none of them caught on.

Today, “they” is the widely accepted pronoun for non-binary individuals. It has come to replace “he” (and even “heesh”) in writing and speech, and can now be used to refer to one person with a neutral or unknown gender identity. However, throughout American history and currently, it continues to be dismissed.

It seems likely that this isn’t just because “they” is ungrammatical – it seems more likely that it is, in part, because humans like patterns. According to the National Library of Medicine, humans developed advanced pattern processing abilities throughout evolution, and these skills were strengthened by emotional and physical experience and learning. Because humans are so skilled at pattern recognition, it’s also understandable that we like categories. And what are pronouns? Categories.

When categories are identified, humans will naturally see differences before we see similarities. Thus, it makes sense that many struggled to change their speech patterns when “they” was introduced in the past decade as both a plural and singular pronoun. Because gender-based categories and stereotypes still exist from when our parents were toddlers, it is still normalized in many parts of the country to see long hair and dresses and immediately think “girl.”

But what must be understood is that when an individual makes a mistake and uses the incorrect pronouns, it may be unintentional. Some people are certainly choosing to not accept the idea of a person being non-binary – a problem that must first be solved before accepting the language change. But for others, myself included, I might make a pronoun mistake out of habit and pattern, not out of disrespect for the person.

It will certainly take time to adapt to these language changes – and it may even take some slight changes to our grammar rules – but they are necessary ones.

At this point, you might be thinking, “why did I just spend time reading an article about grammar?” Sorry about that. I obviously value grammar having written 600 words about it, and I understand that not everyone does. However, at this point in the article, I hope that you are starting to catch on to the message. From our desire to put things into categories to writing off women in grammar for centuries, we are flawed.

It’s a mediocre scenario for everyone. We’re relying on a language that’s founded on imprecise roots, with no sign of change coming anytime soon; many in the country are still stuck on the idea that gender is binary, and many won’t admit that humans are prone to making language mistakes.

Perhaps it is just me who has struggled to understand this issue in its entirety. But as a kid that grew up watching myself and others not sure how to fit in anywhere, I suspect I’m not alone.

“Mediocre” in Latin sometimes translates to “halfway up the mountain.” We – as humans, as Americans, as English-speaking people – are halfway up the mountain. We still have another half to climb.