Have you ever read a children’s book? Hopping from one spectacle to the next, not concerned with plot. Wrapped by the perfect water colors and black pen lines, used to represent people, animals and things that resemble some aspects of human creation. The ending can be separated from the beginning and all you understand is that you left your reality for another in a matter of minutes.

After watching a single movie produced by Studio Ghibli and directed by Hayao Miyazaki, you understand this experience of transportation. Following young men and women faced with death, spiritual lapses or the discovery of a secret, you are briefly afforded the now scarce experience of hand drawn animated art.

In 1979 at age 38, Miyazaki released his first movie, “The castle of Cagliostro.” 44 years later at age 72, the acclaimed director announced his “retirement”, after the release of his final movie, “The wind rises.” This movie seemingly served as a sufficient outlet for personal reconciliation after having a relevant career.

Still, a mere four years later, Miyazaki came out of retirement to begin working on “The boy and the heron.” Shocking few studio members and supporters, as the director had continued to contribute to the studios projects since retiring.

Miyazaki usually works with the same group of animators, himself leading the charge and creating all storyboards. Each movie, although completely cohesive and interpretable, starts production without an agreeable conclusion.

With not a moment of pen to paper, blurred landscapes are spewed with clean cut figures in the foreground, facilitating a meaningful storyline full of personable characters.

The consistent themes, intentionally conveyed by the director in his movies, are those of rebirth, spiritual acknowledgement, natural beauty and grief. The viewer is able to look at plates of food, a pair of shoes, a room, a tree or human connection with an appreciation scarcely applied to the world that surrounds us. The specificity of Miyazaki’s animation style layers this rose colored tint over just about any content the director shares.

When creating “The boy and the heron,” Miyazaki hunted for an animator that could find a new approach that would add to the dissection of the “logic of dreams” this movie attempted to stab at. He beckoned Takeshita Honda, animator and director of “Neon Genesis Evangelion.” Honda had worked on three scenes from both “The wind rises” and “Ponyo,” but found himself reluctant to hold a significant role in this meatier production.

He finds himself falling prey to a looser animation style than what Miyazaki would be willing to produce. Nonetheless, Miyazaki would not take no for an answer and said that he required Hondas skills in order to accurately include a multitude of scenes centered around foggy memories. Honda eventually agreed and became a larger contributor to the final movie than anyone had anticipated.

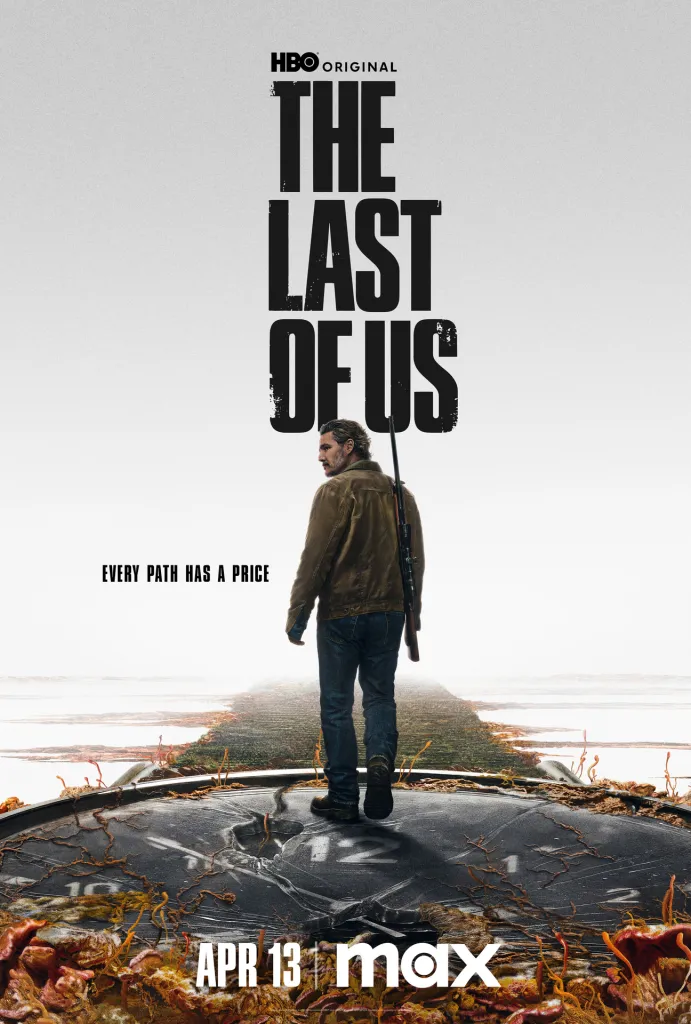

“The boy and the heron,” references the 1937 novel, “How do you live?” The movie follows a young boy, Mahito Maki (Luca Padovan), who loses his mother during the Pacific War in Tokyo. Mahitos’ father, Shoichi Maki (Christian Bale), is an air munitions factory owner who is absent during most days.

This mirrors two parts of the director’s childhood as his father owned the Miyazaki Air munitions factory outside of Tokyo and his mother had tuberculosis and was confined to her bed during his time at home. Shoichi, marries his late wife’s younger sister, Natsuko, who squeezes herself into a parental role for a damaged Mahito.

The scene featuring most of Hondas work occurs in the first sixty seconds of the movie. A watercolor fury swirls around Mahito as he bounds through town among people with apparent broken spirits. They look half dead and without hope as they know the war and fire will consume everything that they love. This scene was deeply impactful and helped make the animation inconsistencies throughout the rest of the movie incredibly coherent.

After a single day at his new school, Mahito finds himself a target and initiates a fight with the boys from his class. When returning home after the fight, he stops, picks up a stone and clubs himself in the side of the head with less than a wince. He walks home with ruby red blood leaking down his sleeve. This action was one of few that felt like Miyazaki. I saw his typical animation style and bravery for depicting the unsettling.

The movie brings Mahito to the forefront of an adventure. He chases his step mother through their backyard and into an old crumbling house. There he finds the Heron and he promises Mahito that he will find his step mother if he travels to another world. Mahito agrees and goes through a portal with one of the older maids from his estate. Once he lands in this nonsensical world he is met with several familiar faces.

Within this atypical world there has been one supreme ruler. He is the mechanic of time, preserving the world as he initially intended. He has created no farmland, no homes, nothing that really resembles human life as it has been. He has added versions of people that Mahito knows now or once knew.

The man is very aged and establishes, as Mahito makes the decision to return to his world, that his time is up. The world begins to crumble as Mahito stands in front of this old man. He begs for Mahito to take responsibility for this world where death can be overlooked, nature is permanent, and where whimsy isn’t limited to anthropomorphic animals. Mahito begins to pull away, for he has responsibilities only found in real life. The man blows one final phrase as his sky begins to fall, “If you don’t take this you will return to your world of murderers and fire.”

During this moment I saw Miyazaki leave us with a reminder to return. His worlds promise so much more than what we get each day. He saw his characters, settings and mythical beasts, amalgamate and crumble in the same lapse. This single interaction defined the movie’s quality.

It made more prevalent and relatable claims about family and motherhood but in general the side characters and plot points felt vague and unimportant. This was a movie that served a purpose of summary. To wrap up a thousand tiny pieces into a poorly cut but cleanly laid puzzle.