Picture a wild western: whiskey, tumbleweeds, guns, thick heads and accents. “Killers of the Flower Moon” has it all, and yet the most infamous weapon this film has in its holster is the gut-wrenching chagrin of truth; it’s a shot rarely fired by an average western on Grit TV.

I’ve read countless articles and questions of “just how much of this is real?” when it comes to this film, because somehow – at a daunting three and a half hour long run time – every second feels the level of insanity that surely only Hollywood heads could come up with.

And yet, this film reveals the reality of the Osage people: a people who had been forced off their freehold by white settlers to the presumably worthless land of northern Oklahoma. Until one day in the beginning of the 20th century, they struck literal oil. Suddenly, the Osage Nation was the wealthiest group in the country per capita, and the very settlers that pushed them off their property were sleuthing for that same substance. And of course, their answer for obtaining this wealth was to marry the people who held it. To have and to hold wealth not their own, till murder did them part.

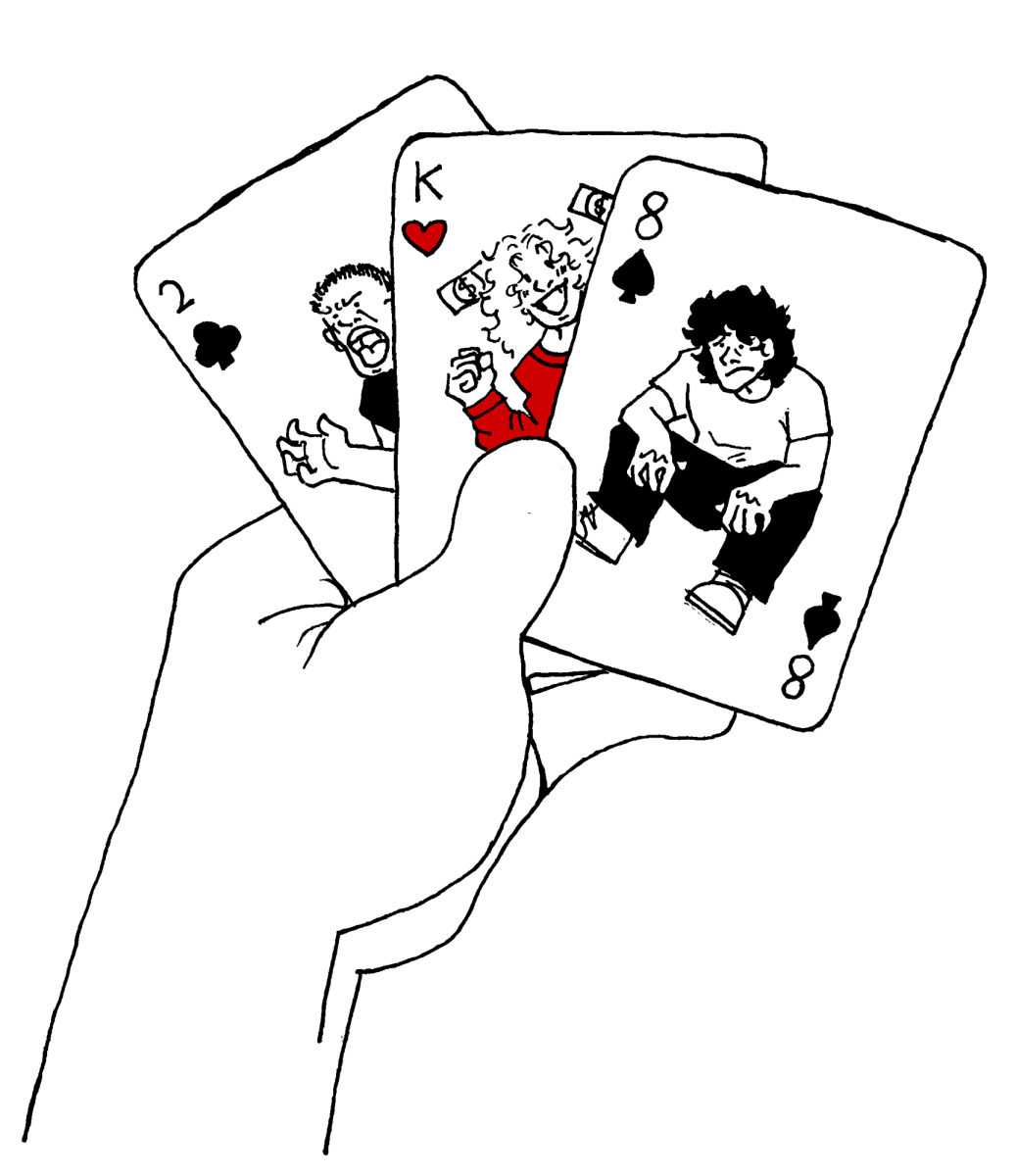

This setting is where we meet our eclectic cast of characters equipt with “King” William Hale (Robert De Niro) a self proclaimed ring-leader of the Osage and everyone he meets, his naive nephew Ernest Burkhart (Leonardo DiCaprio), and Mollie Burkhart (Lily Gladstone) – the one native Osage woman in her immediate lineage that survives this film.

Ernest returns home fresh from war and ready to be worn down by the great “King” Hale’s plan for winning wealth. He takes up a job as a driver in the area for the wealthy Osage, leading him to Mollie. The two marry, and just like everything else that follows it was at Hale’s sly suggestion – just before Mollie’s family and other members of the Osage population are murdered one after another.

This horrific story is often referenced in history as the “Osage Reign of Terror,” which manages to imply that the terrors inflicted on the Osage – where several dozen of their nation were murdered by gunshot, explosives, and mysterious illnesses, or rather, poisonings – were brought down upon them by themselves, when in actuality it was a crime ring of destruction that perpetrated and indoctrinated them into perceiving daily murders as normalcy.

We witness the war waged on the Osage by these white fortune seekers throughout the film, almost entirely from the white perspective. This is easily one of the biggest critiques of this movie: it’s a film that is supposed to give some sort of justice to these people, but still feels like it’s lacking in the strength of their voice.

While I agree with this, I also think Scorcese didn’t make it for them. It was made for all of the people that came out of the theater asking if any of that was real; Americans that likely are blissfully unaware of atrocities like that committed to the Osage. It was made to force the ignorant – myself included – to sit through three and a half hours of not just injustice, but an explanation of how intrinsic instances of violence like these are to wealth and equality disparities we see today. It’s a reminder of just how easily humans can slip into subjugation of those they think lesser than them, and how even more easily we let it happen.

I think of a scene where a storm begins to brush across the plains outside the home where Mollie and Ernest reside, about to partake in a glass of whiskey. When the storm threatens to interrupt this, he goes to shut the window. Mollie tells him not to, and when he questions her, she simply says “we need to be quiet awhile,” for “the storm is powerful.”

They sit in silence for a moment, but he quickly caves as he reaches for the whiskey once more, fumbling with small talk as she shakes her head and laughs softly at his restless inability to remain; like one does to a small child that has so much left to learn.