It was a lofty goal to rewrite the media depictions of Native American people, to atone in some way hundreds of years of not only oppression, but misrepresentation reinforcing that oppression.

From wild-west era depictions of malicious, monosyllabic warriors to primitive, pure and impossibly stoic leaders, there is still hard work to be done in conveying to audiences that indigenous people are not, in fact, a monolith. But it was a task two Native filmmakers chose to take on, vowing to dismantle tropes and playfully subvert expectations at every turn, promising, as show creator Serlin Harjo definitively stated, “No drums, no flutes.”

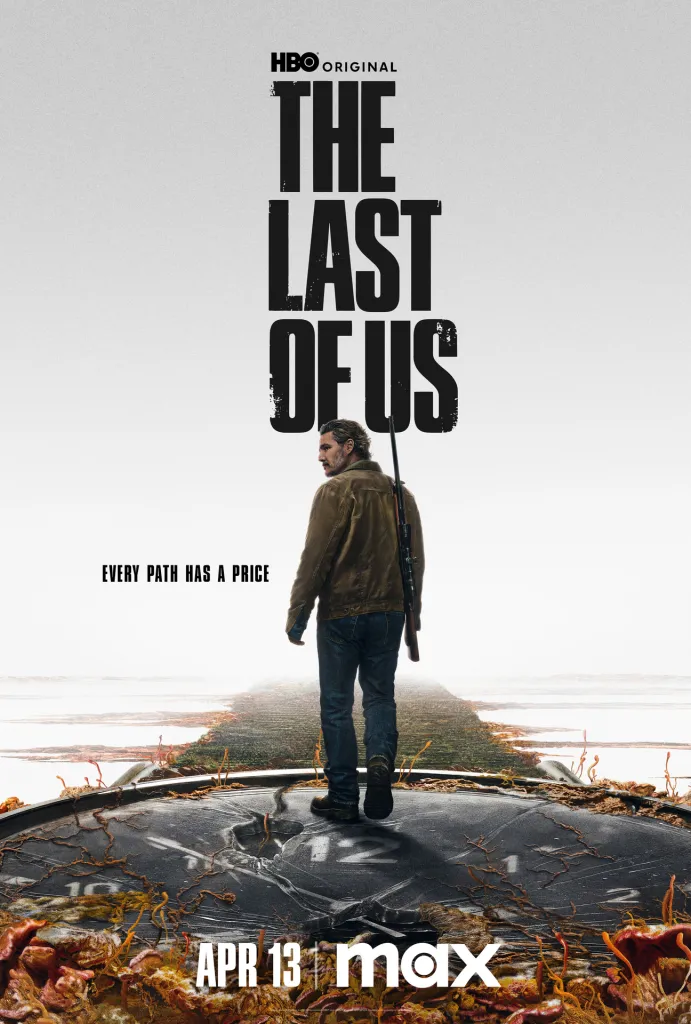

The FX show “Reservation Dogs” wrapped September 27, of 2023 but has left, in addition to a high demand for more diverse dramaties, lingering questions of: What is the most effective way of showcasing diversity? How can we right historical wrongs through our media? And does humor have a place in cultural demonstrations? Inquiries like these are especially resonant as multicultural week at BHS approaches, a time when students will present and celebrate their own cultures through a multitude of authentic expressions.

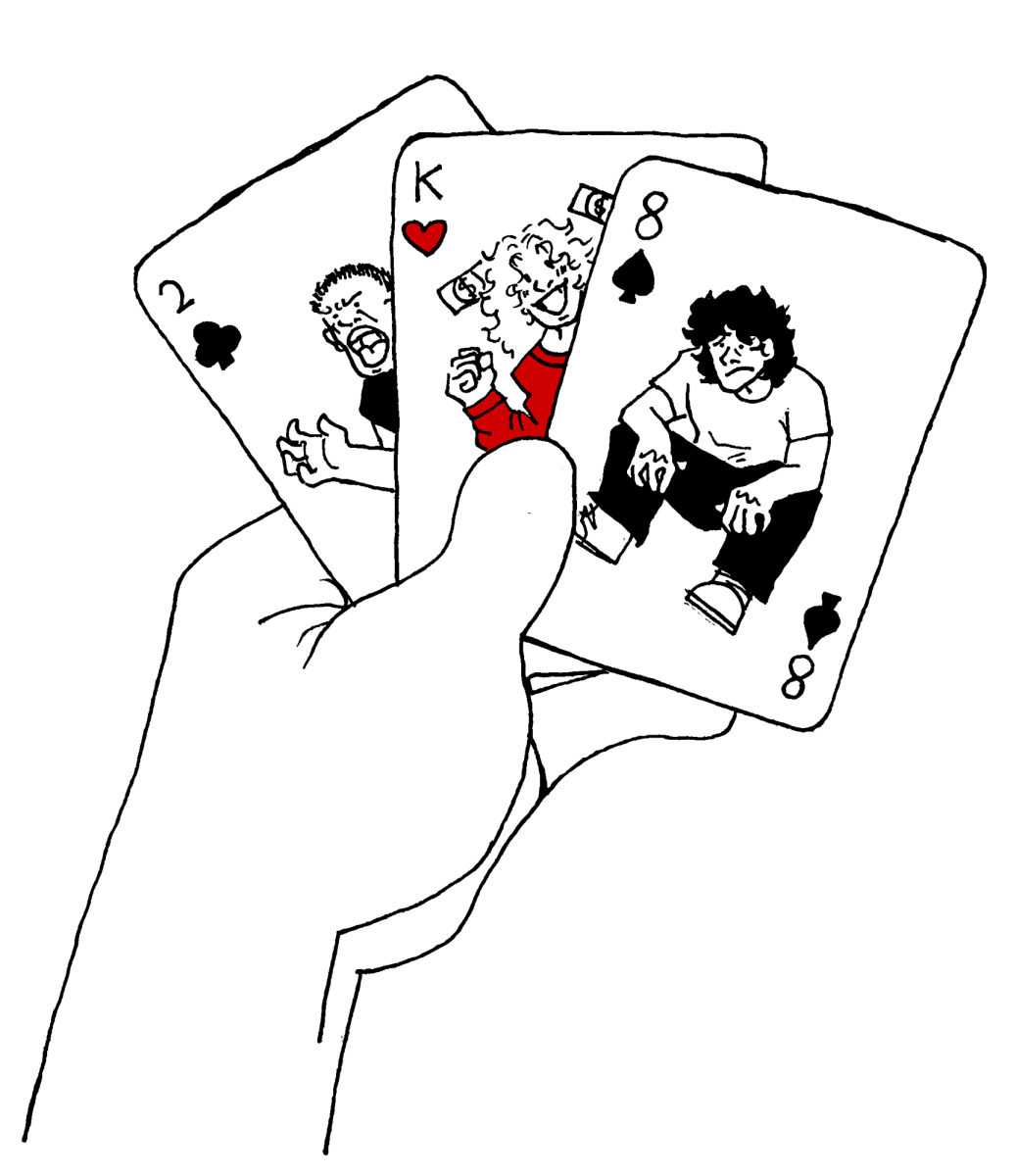

The opening scene of the show– like countless others that establish the uniqueness of “Reservation Dogs” –is playfully irreverent. The self-proclaimed “rez dogs,” consisting of four main characters Willie Jack, Bear, Cheese and Elora Danan, are seen executing the heist of a “Flaming Flamers” chip van. The scene includes frantic hand signals as the group decides when to strike, Bear lecturing Elora on buckling her seatbelt (while driving a stolen van) and sparks flying from the van’s metal ramp as it drags against the pavement, a fate inevitable after Willie Jack failed to detach it before the theft was in motion.

Through the first episode alone, audiences are exposed to a side of indigenous life antiquated movies won’t show you. There is laughter. There is rock and rap music. Gone are the portrayals of Native culture that feel archaic or, at the very least, not contemporary.

However, anyone familiar with life in rural America understands the dichotomy of participating in the pop culture sphere while existing geographically far outside it. This is only intensified by the cultural difference the “rez dogs” (their name derived from living on a Native reservation) feel.

While the pull between popular and traditional remains prevalent as the group expresses desires to live beyond the reservation, the blend of cultures is seamless and refreshingly casual. Characters listen to music by mainstream and underground artists (often showcasing Native ones as well) and speak –in an Oklahoman dialect –a mix of American English and Mvskoke words and slang.

A few terms that diversify the linguistic makeup of the show include, “Mvto,” (meaning “thank you”) “Skoden” (meaning “let’s go then”) and “Cvpon” (an affectionate term referring to a young man, so often directed at Bear or Cheese)

After selling the stolen van to a junkyard run by ridiculous, culturally-appropriating white southerners, the group’s purpose for the theft is revealed: they are saving money to go to California.

The majority of season one’s development for the “rez dogs” centers around plans to “escape” their reservation home and move to California, a dream of their late friend Daniel who committed suicide a year prior to the evens of the show.

The series also explores collective grief in the way each character experiences this loss. Grimly foreshadowing flashbacks breathe meaning into how intense the grief over Daniel is while adding an element of turbulence to the show’s cinematographic style.

During the emotional peak of season one, Elora reflects on her friend’s strange behavior at a honkey-tonk bar on the night of his death and the distress she felt upon discovering his passing. This distress, though not felt as closely by adults who knew Daniel, isn’t exclusive to his four friends. Sadness is felt by the entire close-knit community.

In centering the show around the pain and blossoming growth experienced by the “rez dogs,” Harjo and Watiti not only convey that grief is better resolved together than alone, they also shed light on an upsetting aspect of Native life.

Colonization, discrimination and systemic poverty have led to disproportionately high rates of depression and suicide amoung indigenous communities. In a 2022 interview with Fresh Air, Harjo recalled a day on set when cast and crew members took turns sharing stories of loved ones they had lost to mental illness. Among the primarily Indigenous team of writers, actors and directors, almost everyone had a Daniel.

While this fact is one “Reservation Dogs” doesn’t shy away from representing, Harjo has made his message clear that the indigenous experience should not be shown as depressing or strictly serious. Growing up on a reservation himself, surrounded by laughter and love, he wants audiences to understand the joy of being Native.

Season three –arguably the most concise and well-done season of the show –also skillfully accomplished this juxtaposition of joy and grief. Even with the addition of more serialized and abstract episodes, there is a color and silliness about the show that remains in its characters and world-building.

The episode “House Made of Bongs” was particularly daring as it transported the show’s fictional setting of Okern, Ohklahoma back to 1976, exploring a transformative night in the teenage lives of characters we’re familiar with as elders.

Another utterly transfixing episode was the fragmented “Deer Lady.” A recurring character since season one and a mythological figure in multiple tribes, deer lady is a spirit that defends the vulnerable against injustice, often by killing “bad men.” The episode follows the ominously calculated yet kind-hearted spirit as she helps Bear get home from California following the events of season two.

Through a series of flashbacks, “Deer Lady” tells the story of the titular spirit as a terrified girl forced to endure the brutality of Native American residentials schools. With its letter-boxed vintage look and stark realism, the episode depicts deer lady’s past as if it were an old horror film because, in a way, it is. Her experiences are real-life horror. Another compelling detail was the demonic gibberish spoken by nuns and headmasters of the school, serving as a glimpse into how they would have sounded to Kiowa-speaking children.

A season filled with the deep exploration of characters, introduction of new ones and experimental episodic styles is difficult to wrap up neatly. However, “Reservation Dogs” concluded in the most natural way it knew how: death.

The series closes with the funeral of a medicine man and beloved member of the community. Elders and children gather to cook, give speeches before partially dug graves and make peace with crude, wise spirits in that expectedly unorthodox “Reservation Dogs” way. Words of affection are spoken, teary dialogues between the “rez dogs” are shared as they embark on their young adult lives, yet the message of the episode is seldom spoken aloud.

Between bursts of laughter and mouthfuls of fry bread, a realization dawns on the “rez dogs” : You can’t outsource happiness. It doesn’t come from California, or material wealth or escapist tendencies. It comes from the indestructible sense of belonging that exists within one’s community. So broad, yet simple and sweet, togetherness is the final offering of “Reservation Dogs.” Though, with its earnestness spoken by a voice that is tentative and tough, the farewell sounds more like the “rez dogs’” signature “Love you bitch.”