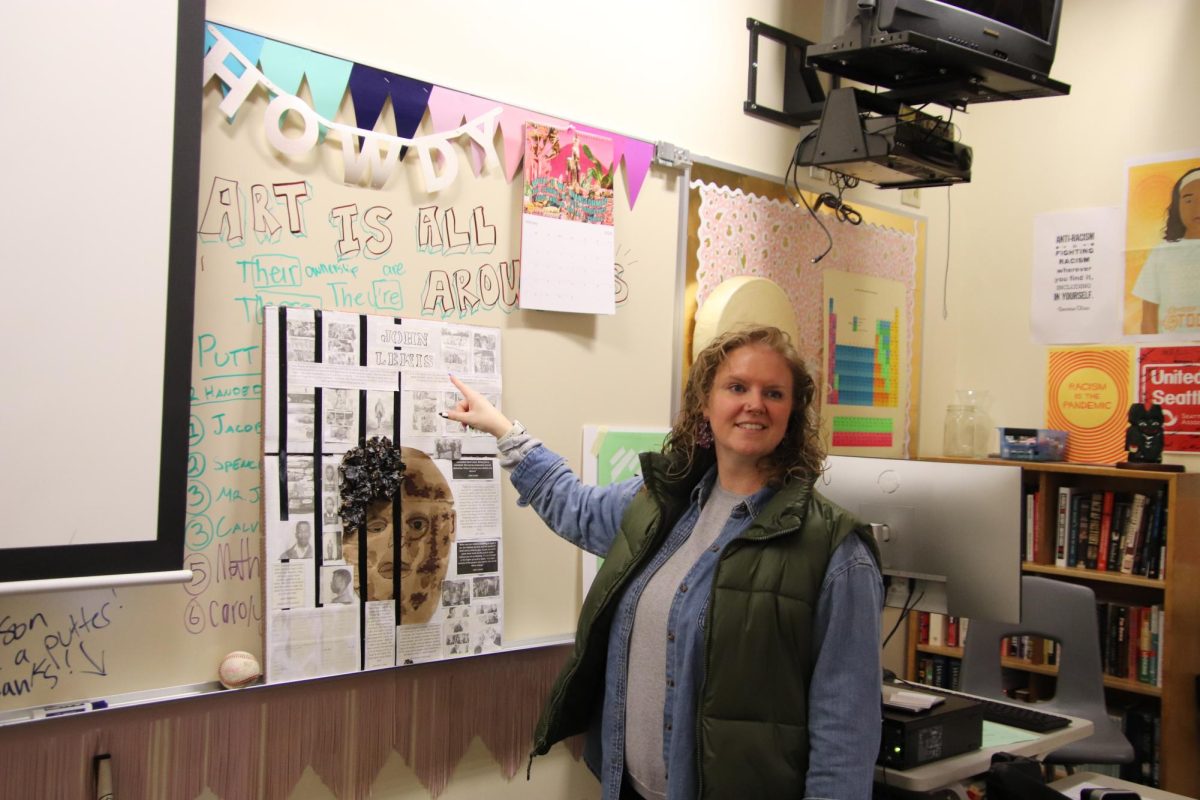

Backed by students from across SPS, with signs reading statements like “Ethnic Studies now, Ethnic Studies always,” Laura Lehni, ELA teacher, ASB advisor and activity coordinator, testified in front of the school board on Feb. 7 about the importance of continuing the 11th-grade Ethnic Studies class. During the testimony, Lehni used both her own words and quotes from her students to advocate for the class and the necessity of its return next year. Administration has confirmed that the course will be returning, but Lehni had worries beyond that.

The Ethnic Studies class is a two-period long hybrid of 11th-grade US History and American Literature that studies history through a language arts lens. The course focuses on diverse perspectives, especially in the sources and texts used.

“When we talk about history, we’re not talking about, ‘Can you list dates, can you prove you read this document?’” Lehni said. “More like, ‘Can you think about this thing and can you engage with the community that you are a part of?’”

The Ethnic Studies class is different from typical history classes in many ways, such as how the information is presented and absorbed. There’s less of a focus on academic competition and more on collaboration and creating a community in the class.

“[Learning] is something that should not happen in bubbles,” Lehni said. “Maybe for a lot of students it’s been a very individualistic or very competitive model of education… and I think that can be harmful.”

According to Lehni, the two-period structure of the course helps form community and bonds between students which helps further their learning.

“People need to be with people,” Lehni said. “People need to be in [a] community and I believe that learning is something that is collaborative.”

Lehni’s worries about the class stem from the lack of support given to it by the district. During the COVID-19 pandemic, SPS was given Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief funds from the government, which they had been using in grants to pay for the Ethnic Studies class.

“[The school district] basically said, ‘We’re gonna give this much money to Ethnic Studies… and then there’s 0$ needed to sustain Ethnic Studies,’” Lehni said. “So right now, at the district, there’s no training, no funding and to my knowledge, no plan to expand Ethnic Studies.”

According to Lehni, it’s not only hard for her to improve as a teacher without support from SPS but also to collaborate with the other Ethnic Studies teachers when they have different prep periods and outside responsibilities. They can struggle to find time to sit down together and discuss the course material.

“You can’t just always build, there has to be time for you to reflect,” Lehni said. “Where’s the time to do that? To not only have an Ethnic Studies class, but really embed ethnic studies in our process as educators and for students.”

Lehni said that the lack of aid being given to the class is hindering its development and harming the people involved with it.

“That’s my bigger concern, to just say, ‘Oh, we created Ethnic Studies,’” Lehni said. “’Now we fixed racism…’ [But] does the system actually make it possible for that to grow and become more integrated?… Because I think having something by name doesn’t equal doing something.”

Lehni’s class has discussions every Wednesday where they sit in a circle and have a space to talk about what they would like to share, related to the course or not. Fellow Ethnic Studies teacher Robin Dowdy held a discussion in her class similar to Lehni’s, where junior Corinne Iacobucci voiced her opinions on the class. She later emailed Lehni, who used Iacobucci’s thoughts in her testimony.

“’In Ethnic Studies, we study the past as a means to inform us on how to build a better future,’” Lehni said, quoting Iacobucci. “’Education about race and racism is the first step toward change. Schools need to provide us with spaces to inform ourselves and reflect on our own actions, because change starts with individuals.’”

Other students came to testify alongside Lehni, such as junior William Souza-Ponce. According to Souza-Ponce, Ethnic Studies is a necessity for all students and belongs in all classes.

“Having a class that focuses on Ethnic Studies is a great intro for kids who haven’t been taught how to approach it and how to view the world through a non-exclusively white lens,” Souza-Ponce said.

Furthermore, Souza-Ponce said that the experiences of people of color are usually taught when talking about pain and trauma. In typical history classes, people of color tend to be brought up only when they can be related to whiteness, such as Black people during slavery and the genocide of Indigenous Americans.

“[Our classes] should include joy and richness and achievements,” Souza-Ponce said. “Scientific inventions, literature, traditions and more, in the same way in which we currently do so with whiteness… Ethnic Studies doesn’t necessarily mean just talking about racism. It means including Black and brown voices in the lessons where whiteness is a given.”