Life, loss and love are the longest and least voluntary battles we will ever fight. And though our struggles may look different, at times feel different in depth and weight, our desire to connect allows us to see kinship in our mutual tenderness. Taking solace in that, as Miriam Toews has put it, “We can come out together in some other, less dark place.”

While most women can relate to the exhaustion induced by a lifetime of fighting for joy, independence and security in the hostility of a patriarchal world, few pieces of literature have managed to capture this experience as tenderly, poignantly and hilariously as “Fight Night” by Miriam Toews.

The novel, based on the author’s real life experiences, is the story of ferocious and unfaltering love between an intergenerational family of women as they fight to absolve their losses, maintain their “sanity” and exist on their own terms.

Like many, Miriam Toews as a writer (and a fighter) has been inexorably informed by her past. Brought up in a strict Mennonite community in Manitoba, Canada, Toews (which rhymes with ‘saves’) witnessed firsthand the shame inflicted upon women and girls by male religious leaders attempting to maintain power and hide their own hypocrisy.

“Fight Night” combats this culture of control by celebrating the resilience of women who have faced the most personal forms of oppression, women who have suffered both loss of love and faith, yet continue to choose joyfulness.

Exploring the traumas of her life through a fictitious setting is not new to Toews. In her best selling novel “All My Puny Sorrows,” the writer fictionalized the difficult end of her sister’s life, who in 2010, committed suicide. Moreover, her penultimately released book “Women Talking” followed a group of women living in a Mennonite village in Bolivia who must navigate living under the subjugation of men, a state Towes finds all too familiar.

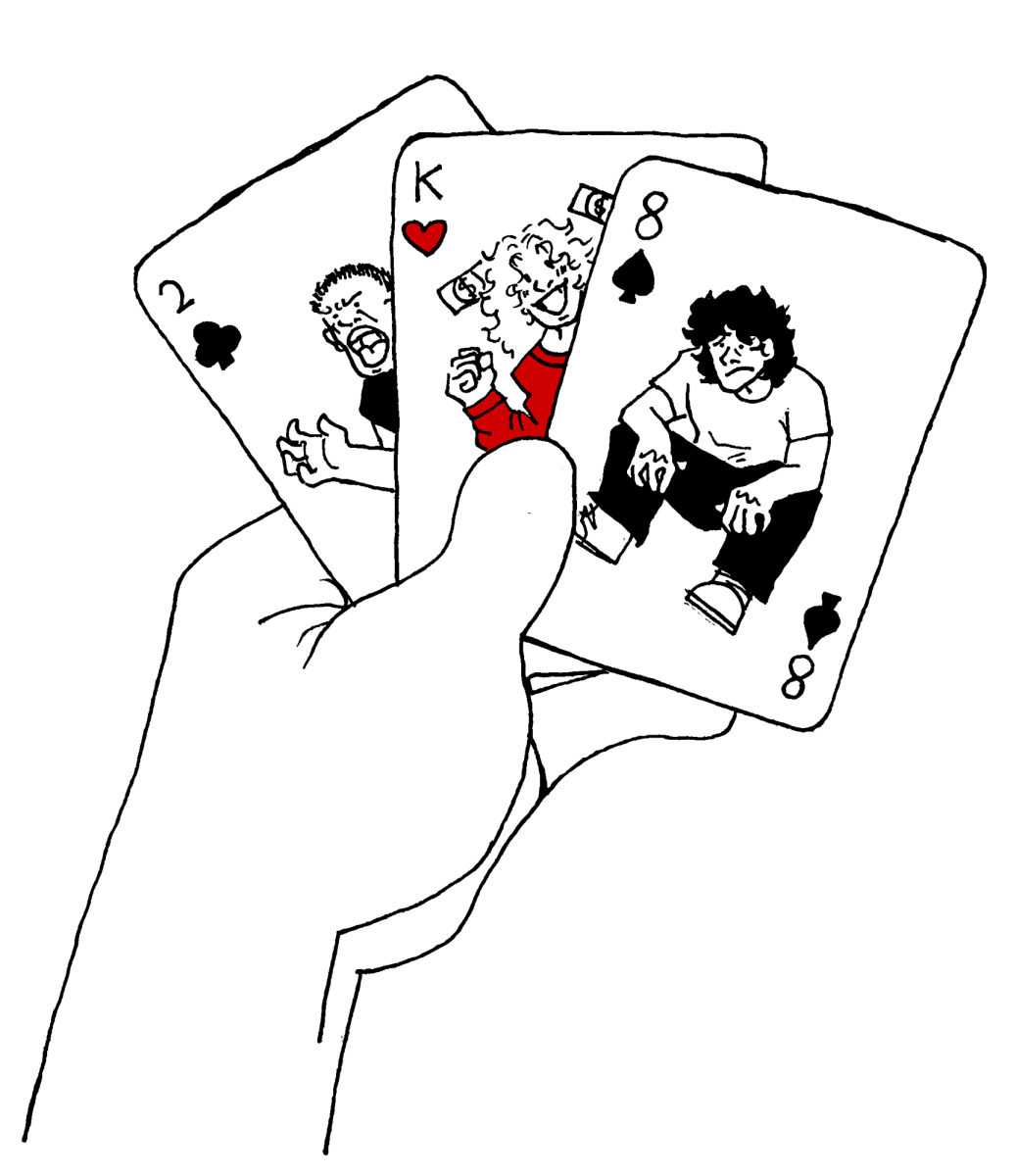

Despite the heavy subject matter, her newest book “Fight Night” maintains a tone that is light and witty. The novel is narrated by precocious and sarcastic nine-year-old Swiv, who, after being expelled from school (due to fighting), decides to write a letter to her recently absent father.

My only real critique of the book would be the slight confusion of this structure. Consisting mostly of dialogue that is either recounted through the voice of Swiv or left unquoted, it’s easy to forget the book is one long letter until Swiv’s dad is mentioned and a startling ‘you’ pronoun appears.

Taking place primarily in the family home, (with the addition of a few zany outings) the first section of the book is light on plot but heavy on absurdity. What initially pulled me in was the effortless way in which Toews can animate the mundane with comedic detail.

This is especially impressive when done through the voice of a nine-year-old, requiring a balance of both maturity and ignorance that is hard to achieve.

Within the first 15 pages of the book, the reader is treated to lines such as, “Mom is having a complete breakdown and a geriatric pregnancy which doesn’t mean she’s going to push an old geezer out of her vag, it means she’s too old to be up the stump and is so exhausted.”

In place of a standard education, Swiv receives lessons in life and “survival” from her grandmother Elvira. Elvira, who was raised strictly religious like Toews, is as cryptic and exuberant as she is unafraid of death while her health declines. Swiv’s mother, nicknamed “Mooshie,” is an actor and in her third trimester of pregnancy.

Between play rehearsals, lingering grief, hormone induced outbursts and her husband’s walking out, Mooshie must task Elvira with what she cannot do on her own: watch Swiv.

However, from the perspective of Swiv, she is just as tasked with watching her Elvira as Elvira is with watching her. From helping her grandmother bathe to sawing her favorite mystery novels into easy-to-hold chunks for arthritic hands, Swiv helps Elvira perform basic functions and is taught practical skills in return.

Mathematically evaluating the time it takes to finish an Amish farm puzzle, writing letters to Swiv’s unborn sibling “Gord” and learning how to dig a ‘winter grave’– to name a few.

Much like the life of Miriam Toews – punctuated by grief through the deaths of her father and sister by suicide – the core of each character’s struggle in “Fight Night” is loss. Mooshie, a mirror image of Towes in this aspect, has lost her father and sister, and is afraid her inherited mental illness will take her from the people she fights hardest to be present for.

Elvira, born the youngest to a large Mennonite family, has trudged forward through loss of family members to physical and mental illnesses, as well as loss of faith at the hands of pompous, authoritative men who twisted her own religion against her, stealing her autonomy and joy in the process.

Finally Swiv, whose age makes her arguably the most vulnerable to loss, fears the loss of her family’s already waning stability. Her dad has already left her for reasons she can’t understand (Elvira says he is “fighting fascists”), her mom, she fears is “insane and will kill herself” and of course, Swiv worries her grandmother’s heart will give out, leaving her all alone.

Yes, behind this novel’s hilarious and mature ‘voice of reason’ are the very real fears of uncertainty, abandonment and growing up.

Though “Fight Night” is peppered with hard-hitting moments of heartache, it’s important to emphasize that it’s a highly entertaining and enjoyable read.

In fact, the majority of the novel’s tools to guide us through anguish come not from lingering on it, but through sharing a full laugh and asking ourselves, “Who can I help?”

For Swiv and Mooshie and Elvira, helping one another has proven the strongest means of supporting themselves. As Elvira writes in a letter to her unborn grandchild, “You’re a small thing, and you must learn to fight.” The sentiment rings true in a world where we all at times feel dwarfed by the enormity of our problems.

A world that steals creativity and power and bliss from right under our noses. A world that requires us to fight for survival, ensuring that the only way to do so is through fists and angry words. “Fight Night” has shown us there is another way to combat hardship. As Elvira says, “Joy is resistance.”