The gold standard of American education

The modern day student knows the process of standardized testing like the back of their hand – the crazed bubbling of a Scantron under fluorescent gym lights is all too familiar.

May 25, 2023

A brief history

Standardized testing traces its roots back to ancient China during the Han Dynasty. The earliest evidence of this form of assessment can be found in the imperial examinations, which encompassed an evaluation of knowledge and skills across various disciplines known as the Six Arts. These included music, archery, horsemanship, arithmetic, writing and proficiency in the rituals and ceremonies of the time.

Fast forward to the year 1900, we see standardized tests become a cornerstone in the American education system. The College Entrance Examination Board was established by 12 colleges, led by the presidents of Harvard University and Columbia University. This board pioneered the concept of standardized entrance tests, which incorporated the evaluation of students’ knowledge and skills across multiple subjects, including essay writing.

Over two decades later, the first Scholastic Aptitude Tests, or SATs, were introduced in 1926. The 90-minute exams had more than 300 questions on vocabulary and math. Then, In 1952, the pilot program for Advanced Placement (AP) exams was established, assessing high school students in 11 different subjects. By 1954, approximately 530 students from various high schools participated in AP exams. These students were required to pay a fee of $10 to take the test, and their performance was evaluated on a scale of 1 to 5. The following year, the College Board assumed responsibility for administering the exams and established the AP program in its current form.

As we know it

The modern day student knows the process of standardized testing like the back of their hand – the crazed bubbling of a scantron under fluorescent gym lights is all too familiar. From SATs to ACTs and AP tests, teenagers understand that these exams play a vital role in their education and the college admissions process. Although many schools have moved towards test-optional policies, a high score can only bolster an application. A 1600 may not be the key to college acceptances, but it certainly gets a foot in the door – it adds a name to the conversation for admissions teams.

A perceived benefit of standardized testing is that it provides an objective measure of student performance. By assessing students using the same criteria and scoring rubrics, it can ensure uniform evaluation across different schools, districts and even countries. This allows educators and policymakers to make data-driven decisions about curriculum, instructional strategies and resource allocation. For example, in 2001, the No Child Left Behind Act mandated that states administer regular assessments in reading and math, disclose the outcomes and guarantee that students attain proficiency levels. Schools faced the potential consequence of forfeiting federal education funding if they failed to comply. Evidently, standardized testing can be a useful resource within the education system. However, these types of exams have evolved into a painful rite of passage that fails to actually support learning.

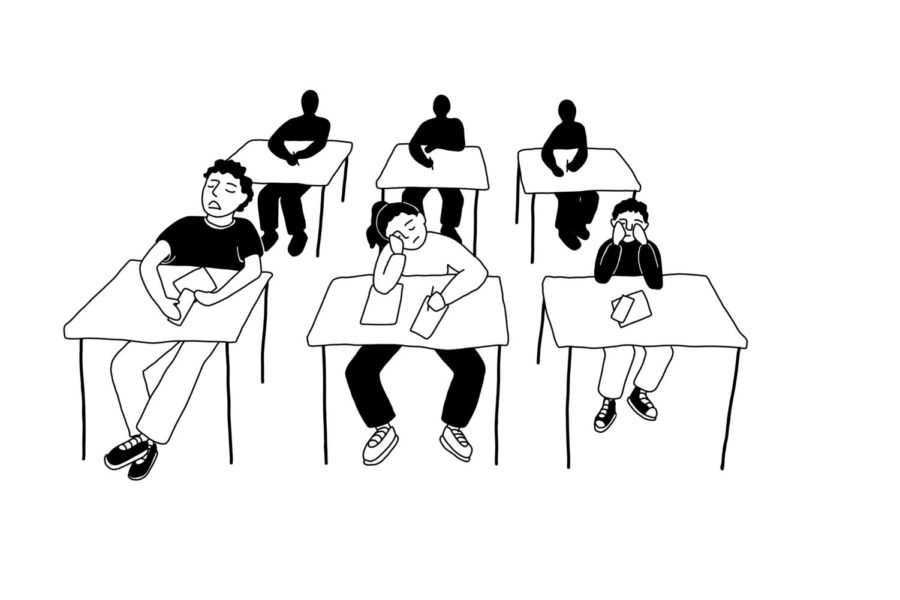

Despite what has been drilled into students’ minds since elementary school, performance in a standardized test is far from being an indicator of intelligence. A major criticism of this type of exam is its focus on rote memorization and regurgitation of information. These tests prioritize the ability to recall the volume of a cone, or the year the Stamp Act was passed, over critical thinking, creativity and problem-solving, which are arguably more important life skills. As AP season descended on high schoolers these past few weeks, this problem became more poignant. To prepare for the exams, students crammed thousands of years of history, or a college-level chemistry course, into just a few weeks of studying. Additionally, much of AP testing is about knowing how to answer AP-style questions and conform to the rubric. Students’ preparedness is also highly dependent on their teacher’s experience and knowledge of the College Board. This results in a style of learning that is unproductive as most of the content will be forgotten soon after the test.

High-stakes testing places immense pressure on young learners. When children are taught that a single test can alter the course of their education, they begin to place their value as an individual on a number. Students will take the SAT and ACT time and time again to break a 1500, or a 33, because scores lower than this are perceived to be worthless in the college admissions process. Opening a disappointing test score has become a gut-wrenching moment rather than a small setback.

Furthermore, standardized testing perpetuates educational inequities. Research conducted by the University of Southern California found that standardized tests like the SAT favor wealthy white students (ironic right?). Students from low-income families, non-native English speakers or those with learning differences face significant disadvantages in these tests because they often lack the resources to access proper test preparation materials, receive specialized support or receive accommodations that could level the playing field.

As we emerge from an era of unprecedented change in our education system, should standardized tests remain, well, the standard? While they can be used as a tool to improve education in the United States, it is critical that we acknowledge their flaws and inherent unfairness. If we choose to prioritize learning and equitable opportunities for all students, then standardizing testing need not remain the standard in our schools.