Iranian immigration lawyer explains the protests taking place in Iran

Tanya Fekri explains the political and historical connotations

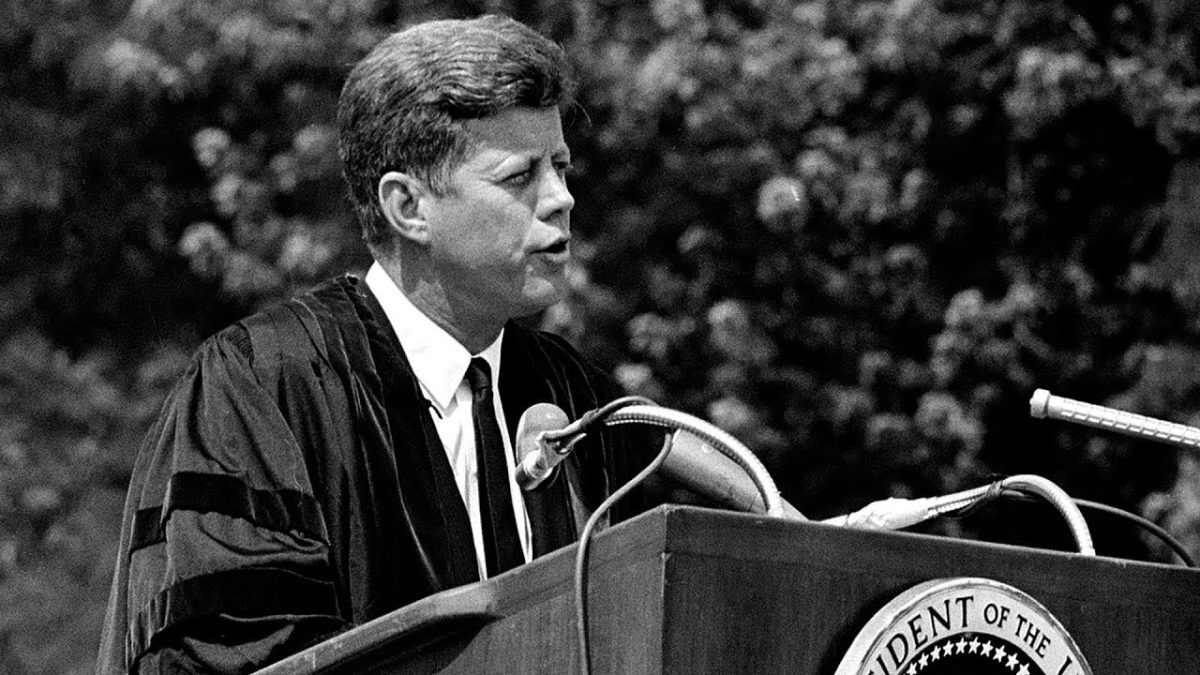

Matt Hrkac via Flickr licensed under CC by 2.0

Demonstrators protest in solidarity with Iranian women after a woman was killed at the hands of the morality police.

November 7, 2022

On Sept. 16, Mahsa Zhina Amini, a 22-year-old Iranian woman was killed at the hands of Iran’s morality police for not wearing her hijab to the standard of the Islamic republic’s dress code. Since then, across Iran, thousands have taken to the streets calling for justice for Amini. According to the United Nations, over 90 members of civil society have been arrested by the government for their involvement in these protests. An estimated 233 have been killed since Sept. 17 when the demonstrations first began.

Tanya Fekri, an Iranian immigration lawyer, was interviewed over email for her thoughts on the issue.

How would you introduce your work? What is your connection to Iran?

I am a licensed attorney in the State of Washington and my area of expertise is in immigration law. I was born in Tehran, Iran and emigrated to the United States with my family towards the end of the Iran-Iraq war. My family and I personally experienced the immigration process first-hand, and that is why I became interested in immigration law. More importantly, my immigration law practice has helped me to work directly with the Iranian community in the U.S. and those in Iran to seek lawful pathways to live and work in the United States.

My source of inspiration and hope stems from my grandmother who will always remain my guardian angel. She was a pious woman who chose to wear the headscarf but was vehemently against government actors regulating women’s bodies and mandating the wearing of the hijab. Her spirit and strength instilled in me and the rest of the women in our family the importance of choice when it comes to making decisions about our bodies and how we choose to express our freedoms.

I have family members who have risked their lives to free Iran and have faced beatings and imprisonment by the Islamic regime for their courageous actions. I come from that line of blood, and I feel an obligation and strong desire to keep the political legacy alive. To that end, it has truly been such an honor to protest alongside my parents and my family members in hopes that our country will one day attain the freedom that our people so rightfully deserve and have been waiting for far too long.

How do you think the protests occurring in Iran today are similar to those that have occurred in the country historically? How is what’s happening now different?

Historically, the Iranian people have always protested for the same reasons – human rights for all, democracy for Iran and freedom. We have now unified as a collective force to fight for the same causes as we have done previously, but what makes these protests even more special is that we are shouting chants such as “zan, zendigi, azadi” (woman, life, freedom), and by doing so we are linking the protest to the broader issues of women’s rights – specifically, a woman’s right to make choices without fear of violence – and targeting the very foundations of the Islamic regime and its ideological taboos.

How would you define the role of morality police to someone unfamiliar with their presence in Iran?

The ideological taboos of this regime are rooted in how women’s bodies should be viewed and controlled under strict religious interpretations. Therefore, the female body has always been at the forefront of the regime’s political agenda. Much of the role of the morality police is to enforce the mandatory dress codes and the state’s gender and sexual proscriptions. Members of the morality police often harass, attack and imprison women in public for not wearing the hijab correctly. In this particular case, Amini died as a result of not wearing her veil correctly which puts the morality police under [a] spotlight.

What does the reaction of Iran’s government, specifically Ali Khamenei tell you about the effect these protests are having nationally. Internationally?

Despite the branding of these protests as “riots” and a U.S. backed conspiracy, Iran’s supreme leader, Ali Khamenei, is recognizing that these current uprisings are threatening the regime’s legitimacy. Many of the religious regulations that are supposedly rooted in Islamic theology are being questioned by all sectors of society, including those who have more religious leanings. The misusing of religion to promote a political agenda that is rooted in abuse, corruption and lies can no longer be tolerated by Iranian citizens and those living abroad. The outpouring of support, protests and activism all around the world are getting us closer to our fight for human rights and an end to the Islamic regime – a dictatorship that has censored and committed heinous crimes against humanity for the last four decades.

What changes social and political, do you think may come as a result of these protests?

Weakening of the regime, abolishment of the obligatory headscarf and a change in political power and makeup that will get us a step (or a few steps) closer to a democratic Iran.

How would you define Iran’s government? How has it changed since 1935?

The most drastic change that has taken place since 1935 was the shift from monarch (Shah) rule to the formation of the Islamic Republic. This revolutionary shift replaced the previous criminal code with the now codified Islamic Penal Code which criminalizes many basic human rights and liberties including the right to freedom of speech and assembly. Before the 1979 revolution, politics and religion remained separated, however, there were some religious scholars and clergymen who held political seats and exerted some political power. After the 1979 revolution, the religious political groups drew out the Shah and implemented a regime change that fought to intertwine religion and politics and control the way society would function and behave. Throughout these last 40 plus years, there have been far too many political prisoners and innocent civilians that have been beaten, tortured and killed by the hands of the Islamic regime.

How is this issue larger than simply wearing a hijab or not?

Yes, absolutely. It is about the freedom of choice – [the] right to choose to wear the headscarf or not to wear the headscarf. It is about living in a country where you have the freedom and liberty to exercise your basic human rights without the fear of violence, torture and/or death.