Staff Editorial

Originally published April 8, 2015

Simon Gibson Penrose

Changes are coming to Washington State education. New requirements for classroom hours, graduation credits and standardized tests mean that schools here will be changing rapidly in the near future.

It is evident that administrators and the state legislature are attempting to improve education. They wouldn’t make changes otherwise. The thinking behind how these specific changes will benefit students, however, is less than clear.

Most of these new policies will make school decidedly harder.

There is nothing inherently wrong with upping the educational ante in terms of expectations for students. The United States needs to compete globally, and in order to continue to do so, its students need to be able to compete as well. Graduation rates need to increase simultaneously with the rigor of education.

High school isn’t supposed to be easy, and we understand that. But that doesn’t mean that graduation shouldn’t be a feasible goal. The recent changes in the form of increased standardized testing and instructional time are actually throwing a wrench in the works.

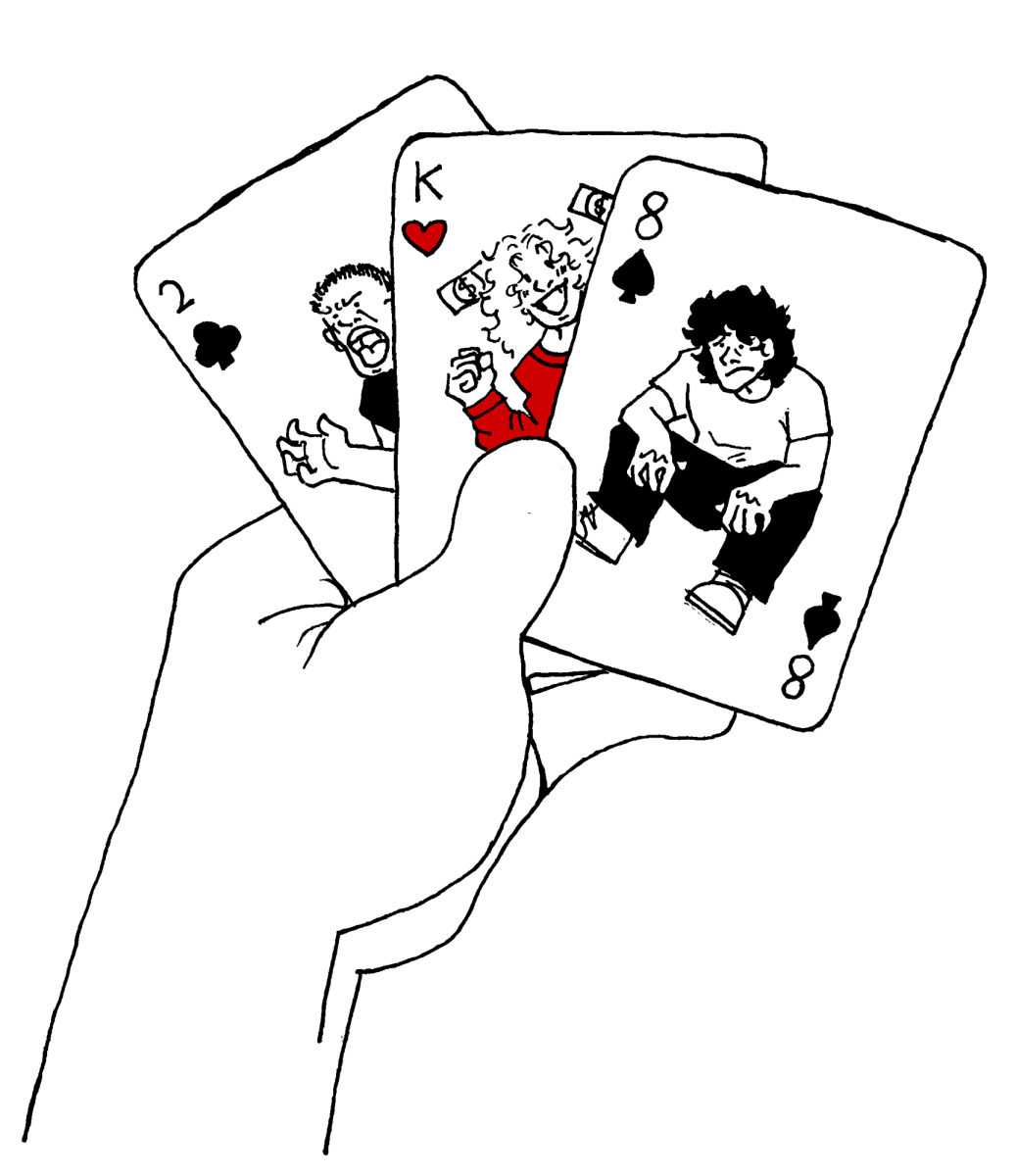

This district’s class of 2021 — next year’s seventh graders — will be required to have 24 credits to graduate, meaning they can not fail a single class. If they do, its credit must be retrieved. At the same time, the administration plans further cuts to the various credit retrieval programs. We’re all for pushing students, but an increase in required credits will only serve to discourage and inhibit students who have a more difficult time.

The newly implemented (and widely dreaded) Smarter Balanced Assessment has been designed to be significantly more difficult than the existing High School Proficiency Exam (HSPE). So much so that approximately 60 percent of students are projected to fail to meet standard.

These sorts of arbitrary additions must be avoided at all cost. A shiny new test that sets a higher bar for students may sound good on paper, but when it comes down to it it isn’t helping anyone. Not the taxpayers that finance it, not the students that take it, not the teachers that have to use up their instructional time to administer it.

It becomes a token, a way to show to constituents and higher-ups that progress is being made without having to change anything. The same goes for longer schedules and tougher credit requirements.

None of this is to say the education system we currently have is satisfactory or working as intended.

On the contrary, change is desperately needed. But it must be comprehensive, well-thought-out change, not desperate grasps for a magic bullet. It must be built from the ground up, not guessed at from the top down.

Until that happens we will be stuck with shot-in-the-dark policies that do nothing but waste and distract.